To old time mountain men, a high mountain valley is known as a “hole.” Jackson Hole (originally called Jackson's Hole) is a valley between the Gros Ventre and Teton mountain ranges in Wyoming.

Wyoming’s population grew slowly before statehood in 1890. It remained relatively untouched and pristine until 1884 when the first white residents arrived. Most were drawn to the towns of Wilson and Jackson.

About the same time, leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) sent parties from the Salt Lake Valley to establish new communities. They were expanding outside of Utah, Idaho and Arizona.

Their timing was excellent. The Homestead Act of 1862, the Timber Culture Act of 1873, and the Desert Act of 1877 all encouraged settlement of the West.

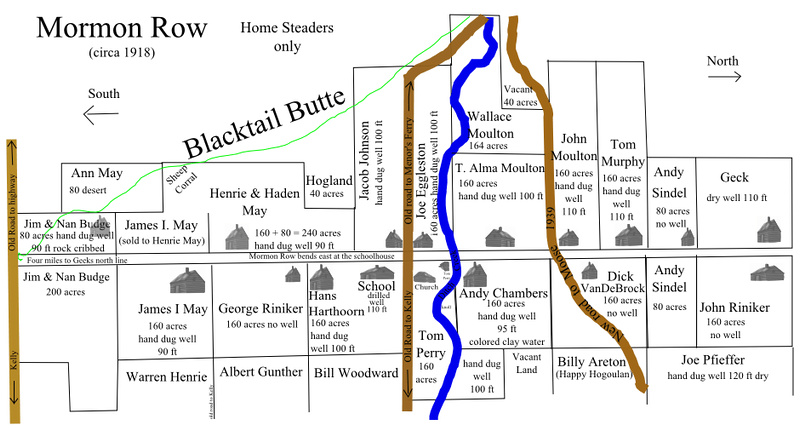

An LDS party selected a location fourteen miles north of Jackson, Wyoming in 1895. It had rich alluvial soil that was marginally better than the rock-filled dirt that covered the rest of the valley. Shelter from the wind provided by Blacktail Butte to the southwest prevented the topsoil from being blown away.

What those pioneers did was unusual. In stark contrast to typically isolated Western homesteads, the LDS homesteaders created a north-south community along a central road. They clustered their farms to share labor and community.

A church and a school were at its heart. Fields and agricultural lands were located behind each of the 27 homesteads. It was named Grovont by the U.S. Post Office after the nearby Gros Ventre River.

Mormon “line villages” such as Grovont were also known as “Mormon Rows” throughout the West. Initially the term was not flattering. Over time, it acquired a positive connotation.

The horse and wagon (sleigh in winter) remained the principal form of transportation in Jackson Hole, even after the introduction of automobiles. This kept the local cash crop of hay and oats economically viable.

Horse and hand labor built an intricate network of levees and dikes to funnel water from the nearby Gros Ventre River to their fields. Water still flows in some of those ditches today.

It was a hard life. A prolonged drought or a hailstorm could mean the difference between barely surviving and bankruptcy. The unpredictable weather caused farmers to diversify into small cattle and sheep operations.

Mormon Row initially flourished and then slowly faded over the span of nearly a century. Parcel by parcel, the National Park Service was gifted or acquired properties as leases expired.

The Shot

Often photographed, the Moulton barn with the Teton Range in the background is a symbol of Jackson Hole, Wyoming. I was looking for a different take on this icon.

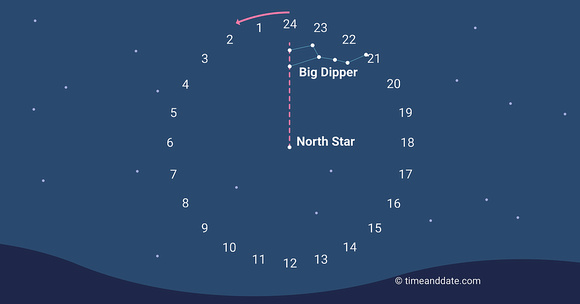

I received a heartwarming birthday gift on the evening of September 25. Our leader, Don Smith, had done the planning for a night shoot at the barn. The Milky Way would be above the barn with Blacktail Butte behind it.

Arriving before sunset, I set up my tripod with my friends, Mike Loebach and Jon Christofersen. When twilight ended and the skies really became dark, we proceeded to photograph the scene and light paint the barn with a small flashlight.

I felt blessed to celebrate my special day under the stars in such a historic location.

Thanks for looking,

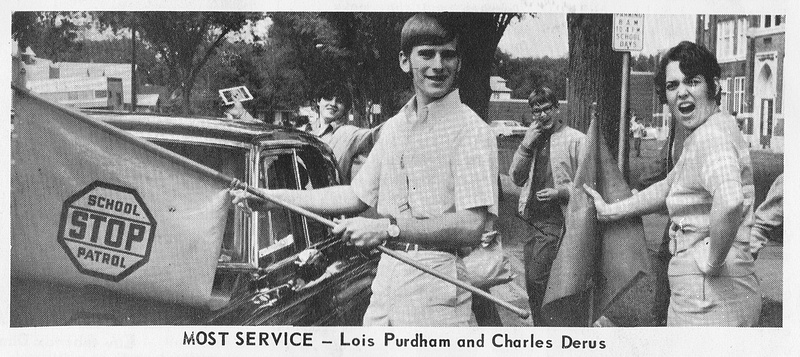

Chuck Derus

Schwabacher Landing is a photographer’s favorite. It’s one of the most popular locations in Grand Tetons National Park near Jackson, Wyoming.

The Landing offers a full, unobstructed view of the jagged, snow-capped Tetons framed by spruce and cottonwood trees. If you arrive before dawn, you can marvel at the glorious sunrise colors playing onto the glowing majestic peaks mirrored in the placid waters of the Snake River at your feet.

The location is named after a family of German immigrant settlers. The Schwabachers arrived in the late 1800s and established a homestead in the area. Beaver dams altered the course of the nearby Snake River creating a tranquil landing.

This boat landing provided vital river access. It allowed fur trappers and traders a means of entry to the remote wilderness and abundant wildlife of the Teton Range.

Over time, the fur trade waned, and Schwabacher Landing transitioned into a homestead and ranching area. Today, it is celebrated for its natural beauty, attracting photographers, nature enthusiasts, and wildlife observers.

It remains one of only four locations in the park where the Snake River can be easily accessed by fishermen, canoeists and rafters. Moose, pronghorn, mule deer, and bald eagles are commonly seen in the immediate vicinity of the landing.

Privately owned tour companies provide guided fishing and rafting trips commencing from the landing. The immediate area is also a popular spot for wedding parties. Above the landing, along the main highway, there are additional vistas of the Teton Range.

The 2010 Shot

I was privileged to first witness a sunrise at Schwabacher Landing back in 2010. I had never heard of it, but the workshop leader said it was a remarkable, hidden gem.

Out of the ten photographers on that 2010 workshop, only friend and fellow photographer Jon Christofersen and I joined our leader for a last morning of photography at Schwabacher. The rest were too exhausted and slept in.

After a short walk, we arrived to find a non-photographer sitting in a folding chair waiting to enjoy the sunrise. Jon and I set up our tripods in the tiny landing space and composed our shots. A little later, another photographer arrived, and we weaved our tripod legs together to make room for him.

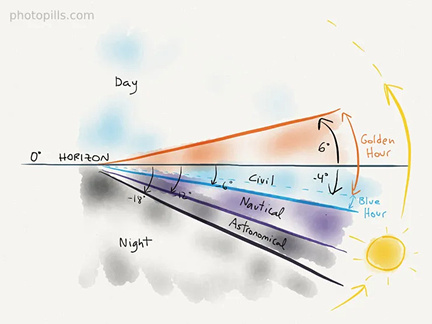

The sky was severely clear (boring) that morning, so my favorite image was taken in the blue hour and featured star trails.

The Shot from September 23, 2024

When I returned to Schwabacher Landing with friends Jon Christofersen and Mike Loebach last month, we were again the first to arrive. After that, we noticed some differences.

The Landing had been cleared with room for dozens of photographers. And as dawn approached, the space was filled with camera buffs.

After taking this Friday’s Photo, we packed up and walked back to the parking lot. There must have been a hundred photographers lined up along the Snake with an equal number of tourists with camera phones enjoying the show. How times have changed.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Country roads, take me home

To the place I belong

West Virginia, Mountain Momma

Take me home, country roads

John Denver, from “Take Me Home, Country Roads”

Country Roads

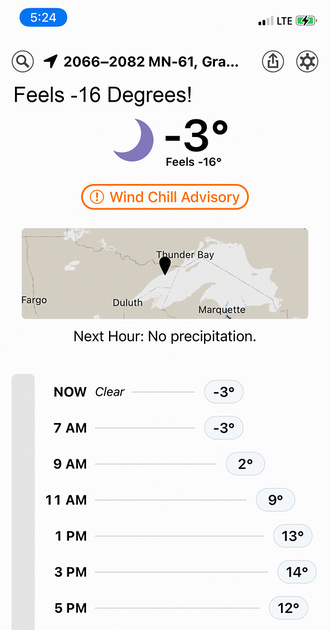

Childhood memories run deep. Growing up in Minneapolis, my family often headed north to explore the Arrowhead region of Minnesota. I vividly remember taking the back roads, especially in a time when President Eisenhauer’s dream of an interstate highway system was just beginning to be realized.

The further north you traveled, the more rustic it became. Grand Marais, near the Canadian border on Lake Superior, was a sleepy little town. From there, you could drive into Minnesota’s wilderness on the Gunflint Trail, a dirt road.

John Denver’s 1971 hit, Take Me Home, Country Roads, is now one of the four official state anthems of West Virginia. But the inspiration for the song had nothing to do with West Virginia.

The inspiration struck while songwriters Taffy Nivert and Bill Danoff were driving along Clopper Road in Montgomery County, Maryland. Danoff stated, "I just started thinking, country roads, I started thinking of me growing up in western New England and going on all these small roads. It didn't have anything to do with Maryland or anyplace."

The Shot

Two weeks ago, I found myself on the Honeymoon Trail Road in the back country near Tofte, Minnesota. Suddenly, I was flooded with memories of my childhood vacations in the north woods. The country road had taken me home.

When our photography group saw the road curving nicely to the right and out of sight, we stopped for a picture. The road sign seemed to be the perfect counterpoint to the brilliant distant tunnel in the leaves where the road disappeared.

As with most rural signs, it had a few bullet holes. Actually, twenty-four bullet holes and two shotgun hits.

After taking this image, I wandered up and down the road in search of a better composition. After about an hour, we realized that the first image was the best and we piled back into the car seeking other compositions.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Summer is over and winter hasn’t yet arrived. Do you call this season autumn or fall? And why does it have two names?

The names of our two extreme seasons, winter and summer, are very old words. The reconstructed Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language originated from around 4500 BCE to 2500 BCE in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Summer comes from the PIE root sem, which means half. This suggests that in Europe, there were originally only two seasons. The root sem transformed into many similar words such as sumor, sumar, and somer.

Winter comes from the PIE root wed, which means water, wet, or rainy. It was similarly transformed with the English word winter coming from the Proto-Germanic wintruz.

The other two seasons are relatively recent additions. There were no distinct English words for spring or fall until the 16th century.

Descriptions of springtime first appeared in Early Modern English, from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Numerous words such as vere, primetide, and lenten described springtime. According to Earl R. Anderson in his book Folk Taxonomies in Early English, this variety of terms suggests spring was unimportant compared to winter and summer.

The same applies to fall. It was sometimes described as the time for harvest, but harvest referred to an activity and not to a season.

Autumn first appeared in English around the late 14th and early 15th centuries. It coexisted with harvest as a loose description of the season for another 200 years.

Fall first shows up in the mid-16th century in England as the fall of the leaf, which was shortened to just fall. Like harvest, it was descriptive. But it also evoked a poetic sense of what made this season different.

The recognition of fall/autumn as a distinct season started in England at the same time the American colonies began to separate linguistically from British English.

Noah Webster, of Webster’s Dictionary, was an ardent spelling reformer. His work was sensible and logical (center instead of centre, for example). But he was also politically motivated to differentiate American English from British English. By the mid-19th century, Americans commonly used fall and the British commonly used autumn.

The Shot

Last week, friend and fellow photographer Jon Christofersen and I walked into the Hovland Woods Scenic and Natural Area near Grand Marais, Minnesota. We were in search of fall color.

The Woods are home to over a dozen native plant communities. Aspen-birch forest blankets roughly half of the 1,280 acres. Because nearby Lake Superior moderates the climate affording cooler summers, milder winters and higher humidity, a sugar maple hardwood forest can exist there.

After a pleasant hike, we arrived at the sugar maple forest. We had the occasional reds we were looking for to compliment the vibrant yellows, oranges, and greens of other leaves and the blue of the sky.

Pointing our cameras upwards and using the edge of a tree to produce a sun star, we rejoiced in being there and in capturing some of Minnesota’s beauty.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Last looks are often memorable. This one is forever etched in my memory.

It was November 11, 2023, our last evening of photography in Pakistan. I was standing with our photography group on the side of a dirt road just outside the remote village of Chaprot at over 9,000 feet above sea level.

There was a chill in the air. It was late fall, and when the sun dipped behind the ridge to our right, my jacket and hat provided me with a soothing warmth.

We peered into a picturesque valley and off into the distance. A small stream served as a striking photographic leading line transporting the viewer to a distant, compelling mountain peak.

It was Rakaposhi. The sight commanded our rapt attention. The mountain is simply spellbinding.

It’s the only peak on earth that descends directly and without interruption for almost 20,000 feet from its summit to its base. Rakaposhi is also the only mountain in the world rising directly from beautifully cultivated fields to its dizzying height of 25,550 feet.

It’s a tough climb. The first successful recorded ascent wasn’t until 1958 by Mike Banks and Tom Patey, members of a British expedition. It took another 21 years before the second team reached the summit in 1979.

If you decide to climb Rakaposhi, base camp is a record 16,400 feet below the summit. Every other tall mountain in the world has a shorter climb from base camp.

The Shot

We waited until the sun kissed just the top of the peak. I’m sure I looked less than graceful taking the picture. Placing the tree on the left in the ideal part of the frame required me to stand on my tippy toes on a small rock near the edge of a drop-off with the camera held as high as possible over my head.

It took several attempts before everything was in the frame and level. You’re probably laughing, but you try it!

We just stood in admiration as the mountain gradually lost its illumination. Finally, it was time for high fives, handshakes, and hugs as we reluctantly concluded our trip and prepared to start the journey home.

The downhill drive out of Chaprot to the highway took several long hours on a sketchy dirt road. It was several more hours until we arrived at our hotel for a good night’s sleep. But Pakistan was worth every minute of our arduous travels.

If you want to see a 39-second video of the start of our drive back to the hotel, it’s at Zenfolio | Chuck Derus | Pakistan

I’m on vacation for the next few weeks, so the next Friday Photo won’t be until October 11.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Vulcans are the fictional extraterrestrial species in the Star Trek franchise. Noted for their pronounced eyebrows, pointed ears, strict adherence to logic, and a distain for emotion, they are from the fictional planet Vulcan.

The most notable Vulcan is Spock. He was first played by actor Leonard Nimoy in the original 1966-1969 TV series Star Trek. The three-year, eighty-episode series inspired an additional fourteen TV series and an equal number of movies.

Star Trek is a 2009 motion picture prequel to the original TV series. The 11th film in the franchise was written as a reboot that spawned two sequels. It featured the main characters of the original TV series portrayed by a new, younger cast.

Swell Times

If you watch the movie, you'll be seeing Utah scenery. Scenes of Spock's home world Vulcan were shot in the San Rafael Swell. It’s the same San Rafael Swell from last week’s Friday Photo.

The movie crew spent five days filming in the Swell. This wild country of barren rocks, dagger-like peaks, and hidden canyons made for a perfect alien planet.

Watch the scene where Spock witnesses the antagonist Nero destroy Vulcan. You’ll see the silhouette of the San Rafael Swell peaks disappear into the misty distance.

The Shot

In March of 2023, friend and fellow photographer Jon Christofersen and I hiked into the Swell’s Ding and Dang canyon trail. After scrambling a hundred feet up to a ridge, we launched our drones and started exploring.

I began looking west, but when I turned east and saw the rising sun, I knew I had my shot.

The next Friday Photo will be September 20. I’m taking next week off.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

At age 23, with no real qualifications and limited formal education, Abraham Lincoln ran for his first Illinois political office. Following an initial loss in 1832, Lincoln subsequently served four terms in the Illinois House of Representatives.

In 1836, after borrowing and reading books on the law, he received his Illinois law license. On April 15, 1837, Lincoln moved to Springfield, Illinois, to practice law with John Todd Stuart.

It’s also where he met Mary Todd. In the fall of 1842, they decided to marry despite the opposition of Mary’s family.

He set his sights on the U.S. House of Representatives and was elected to his only term there in 1846. In January 1849, before his term ended, he proposed an amendment to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. When his term ended, he returned to Springfield.

In 1854, Lincoln won a fifth term in the Illinois House of Representatives but decided to run for the U.S. Senate instead. He lost to Stephen A. Douglas.

Then came the Republican National Convention of 1860 and the rest is history. On a rainswept morning of February 11, 1861, Lincoln left for Washington, D.C. He did not return until May 4, 1865, when his funeral train’s somber journey finally ended in Springfield.

Sight Seeing

Last week, my wife Christine and friends Deb and Win Wehrli visited Springfield and the Illinois State Fair. Our first afternoon found us visiting the Illinois Capitol Building, the Illinois Supreme Court building, the Lincoln Presidential Museum, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Dana-Thomas House.

Me, my wife Christine, Deb Wehrli, and Win Wehrli

Coming from Minnesota, this was my first visit as a tourist to Illinois’ capital. In the late 1990s, I made several work trips to the Capitol building to “work the rail” lobbying legislators in my former role as chair of the Illinois Association of HMOs Medical Directors Commission.

What captivated my attention last week was touring the Illinois State Capitol Building. I kept imagining a young Lincoln honing his political skills in that very building.

His words came to mind. “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.”

The Shot

The featured image is looking up 361 feet to the dome of the highest non-skyscraper capital building in the U.S. It’s even higher than the U.S. Capitol. It’s framed by the outstretched arms of a sculpture of a woman.

The sculpture represents "Illinois Welcoming the World." A plaster statue, by sculptor Julia M. Bracken, was first displayed in the Illinois Building at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. The sculptor was then asked to reproduce the statue in bronze for the Capitol. It was dedicated on May 16, 1895.

My second favorite photo is the Illinois House of Representatives chamber. Again, my thoughts went to Lincoln.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

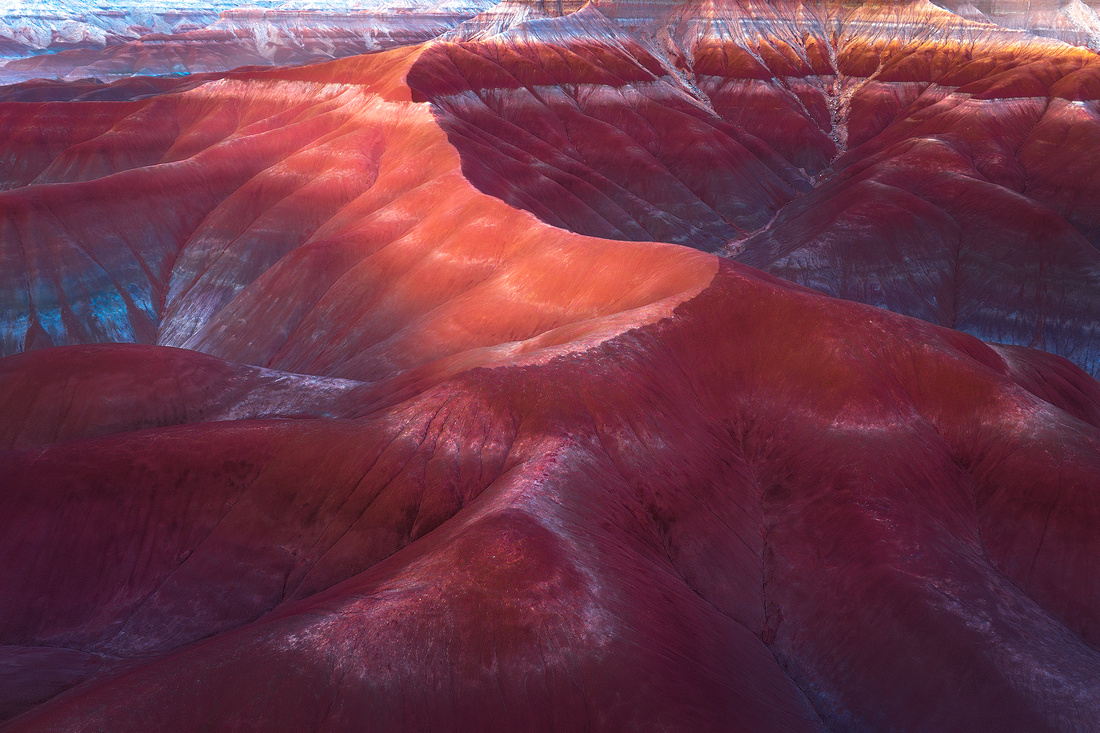

A Kaleidoscope of Colors and Shapes

The San Rafael Swell offers a visitor an abundance of geologic marvels. It’s located in Emery County in central Utah. Part of the Colorado Plateau, it extends for approximately 75 by 40 miles.

You can thank an orogeny for this formation. That’s the process where a section of the earth's crust is folded and deformed by lateral compression to form a mountain range. Created 40 to 70 million years ago, the Swell is home to variegated desert colors and shapes.

Layer upon layer of colorful ancient blue-gray shale, greenish limestone, reddish Wingate sandstone, and golden-buff Dakota and Navajo sandstones cover the landscape. And erosion has created tall fins, domes, cliffs, and deep canyons.

The Shot

In 2023, friend and fellow photographer Jon Christofersen and I set out for the Southern part of the Swell near Goblin Valley. We made our way for a few miles along the Ding and Dang Canyon trail and then ascended about one hundred feet to a ridge.

From there, we had the necessary line of sight for control of our drones. We flew to a promising location about a mile away. After arriving, I felt like a kid marveling at a kaleidoscope for the first time.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

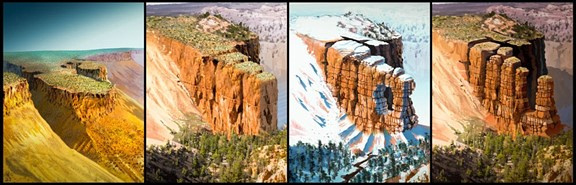

Have you ever felt like you could walk into a painting or a photograph? And did you linger in rapt attention, eyes moving throughout the image? I experienced this recently.

Bill Hughes (1932-1992) Canyon Passage 1991 Oil on Canvas

I was in Marietta, Georga in June visiting friends John and Joann Vineyard. They suggested a visit to the nearby Booth Museum of Western Art. This painting stopped the three of us in our tracks. We felt compelled to “walk into it” and linger.

The 3-D Challenge

Grabbing and maintaining interest in a two-dimensional landscape image requires conveying a sense of depth. You need clues to spatial relationships.

Painters start with a blank canvas and add clues to convey depth. It’s a distinct advantage.

But photographers must choose complimentary subjects and then coherently arrange them in the field. And processing the image in Photoshop™ is often necessary to enhance a sense of depth.

It isn’t always possible. Sometimes photographers reluctantly move on from beautiful scenes because they didn’t convey depth.

Atmosphere is an ally. The sense of three-dimensionality in last week’s Altit Fort photograph was due to atmosphere. The smoke separated the Fort from the distant mountainside creating a sense of distance.

Dust, fog, smoke, and clouds cause objects in the distance to become less distinct, lighter, and less saturated compared to foreground objects. Those clues to distance quickly attract photographers to the subject and viewers to their images.

The Shot

This was taken just after the Altit Fort photograph from last week’s Friday Photo. I had my telephoto lens attached looking for a way to use it to my advantage. A telephoto lens compresses perspective, making objects appear closer together.

After spotting the compressed repeating triangle shapes of the mountainsides retreating into the hazy distance, I knew I had my composition with those much-needed clues to depth.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

The Hunza Valley is tucked away among the precipitous peaks of the Karakoram Mountains in northern Pakistan. Its natural splendor and position on the Central Asian Silk Road have attracted travelers, merchants, and trekkers for centuries.

Beyond its jagged peaks, glaciers, apricot farms, and turquoise lakes, the Hunza is also rich in cultural heritage. Such is the case with Altit Fort.

The People of the Hunza

The origins of the Burusho people in the Hunza realm remain a mystery. Interestingly, the local language has no known links to any other language. So, where did they come from?

According to legend, Altit village was once known as Hunukushal, which means “village of Huns.” Some claim to be descendants of Huns who arrived in the first century from the Huang-Ho valley in China. Others believe themselves to be descendants of Alexander the Great's Greek soldiers.

Over time, the name of the village changed to Broshal, which means “village of Burushaski speakers.” The people of the village used to follow Buddhism and Hinduism until they were introduced to Islam in the 15th century. In the 1830s, many of its inhabitants embraced the Ismaili sect of Islam.

The Tower and the Fort

The hereditary rulers of the Hunza state are titled Mir. One of them built the Shikari Tower (the first part of the Fort) 1100 years ago. Home to the Royals, the Tower monitored and defended caravans traveling on the Silk Road.

In the 16th century, the local prince married a princess from Baltistan who brought craftsmen to build Altit Fort and nearby Baltit Fort. Subsequently, the Mir and his family moved to Baltit Fort.

Located 1000 feet above the Hunza valley, Altit Fort has a commanding view of the area. The Fort survived centuries of enemy attacks and earthquakes. The builders truly deserve the term craftsmen. The Fort is so well built that it can survive an 8.5 magnitude earthquake!

It wasn’t until 1972 that Hunza transitioned from being a princely state to becoming formally part of Pakistan. Altit Fort is now a popular tourist destination after its restoration by the Aga Khan Foundation in 1990. The museum provides significant insights into the lives of the Mirs and the Royals that lived there.

The Shot

Structures normally don’t interest me. Landscape is my passion. But occasionally, something manmade captivates me.

We drove to a ridge overlooking the Fort last November 11th. Below us, the wonderous Altit Fort dominated the countryside. Wood smoke from thousands of breakfast cooking fires shrouded it in mysterious light.

I must thank photographer Atif Saeed and guide Muqeem Baig for sharing the Hunza with us. While the scenery was gorgeous, their friendship made it a special experience.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

What’s the story of this famous brand’s logo?

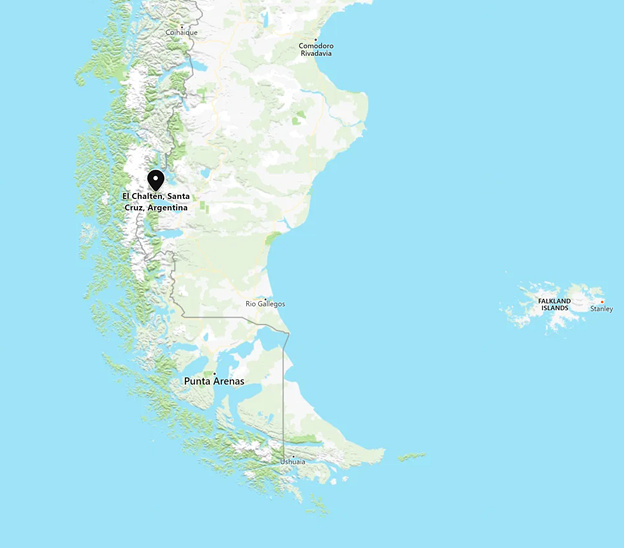

The Patagonia® logo is an Andes Mountains skyline at sunset. The iconic peak right of center is Mount Fitz Roy, located on the border between Argentina and Chile in the region of Patagonia.

The brand’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, began climbing as a fourteen-year-old in 1953. In 1957, he started forging his own chrome-molybdenum steel climbing pitons. They were an excellent product and soon he was in business.

In 1968, Chouinard climbed Fitz Roy. By then, he was concerned about the environmental impact of steel pitons fracturing rocks. He invented aluminum chocks that could be wedged by hand rather than being hammered in and out of cracks.

The first Chouinard Equipment catalog appeared in 1972. Sierra climber Doug Robinson promoted the chocks. Within a few months, Chouinard’s chocks replaced steel pitons.

His Patagonia® company and logo were officially launched in 1973. To support the marginally profitable chock business, his company expanded into clothing – and the rest is history.

The Man Behind the Mountain’s Name

Spanish explorer Antonio de Viedma was the first European to see the mountain in 1783. Argentine explorer Francisco Moreno later named it in honor of British Vice Admiral Robert FitzRoy.

FitzRoy was captain of HMS Beagle. The most famous voyage of the Beagle was its five-year second voyage from 1831 to 1836. His ship carried the recently graduated naturalist Charles Darwin around the world.

Vice Admiral FitzRoy from reddit.com

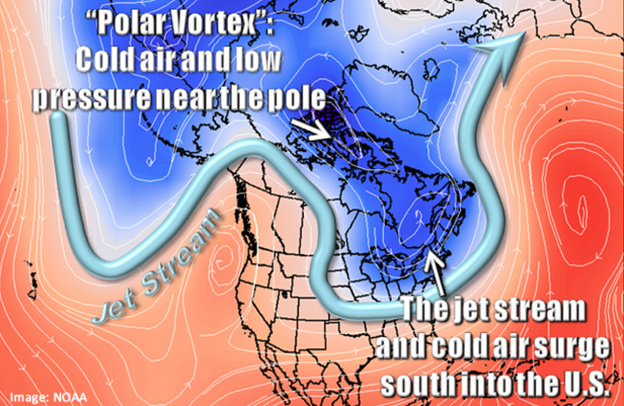

FitzRoy was also a pioneering meteorologist. He made accurate daily weather predictions and coined the term "forecasts."

In 1854 he established The Meteorological Office, the United Kingdom's national weather and climate service. To this day, the Office provides weather information to sailors, fishermen, and the public for their safety.

The Shot

Patagonia is famous for its winds. They seldom abate. Reflection images require calm conditions and are usually out of the question in Patagonia.

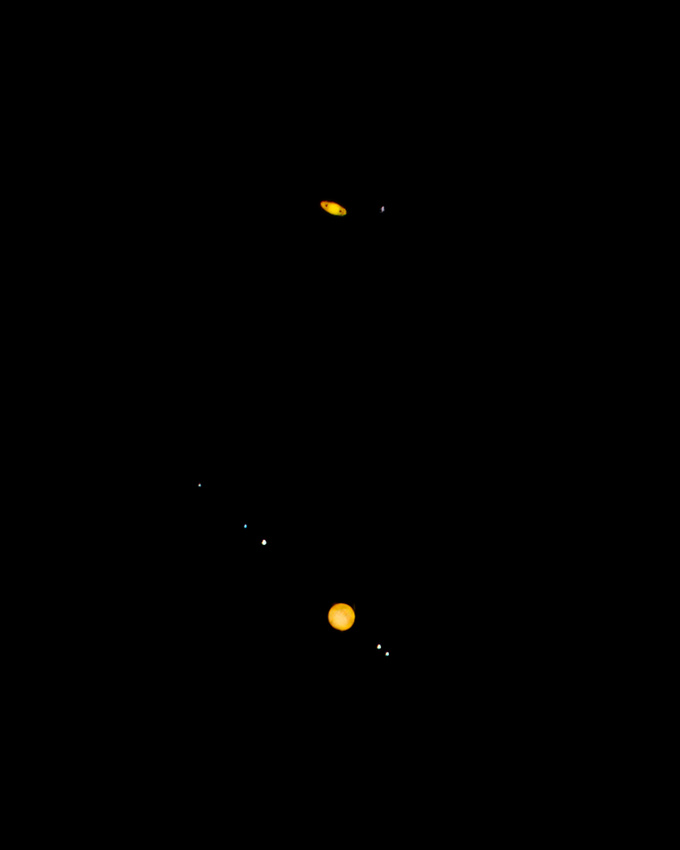

Imagine my surprise when I woke up last April 11. It was calm! Our group drove to a location just outside Los Glaciares National Park near El Chaltén and launched drones.

We were astounded to see a perfect reflection of Fitz Roy in the Río Cañadón de los Torres. We quickly captured images as we worried about a sudden return of the winds. But our luck prevailed, and we were able to fly for a full thirty-minute battery life.

I felt doubly blessed returning to our hotel for breakfast. On my first trip to Patagonia a decade ago, I also had the rare opportunity to capture this reflection image.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

“A stunning place where glaciers fall from the peaks to the sea, turquoise lakes abound, and carnivorous plants guard the entrance to mysterious mountain valleys.” That’s how @patagoniavertical describes the Cordillera Riesco Mountain range

The Grupo La Paz rock towers are the centerpiece of the Riesco. Located in Chilean Patagonia to the west of Puerto Natales, they extend in a north–south direction on the eastern shore of the Fjord of the Mountains.

Aguja Oeste at 3,900 feet is the highest in Grupo La Paz. The tower was first climbed in 1988 by Yvon Chouinard and Jim Donini. One of our guides on the photography charter boat recently traversed the Grupo. Antar Machado was the expedition’s photographer.

Antar’s route traversing the Grupo La Paz. From REGION MAGALLANES - CORDILLERA RIESCO - Grupo... - Patagonia Vertical | Facebook

You can read about Antar’s expedition at https://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/13201216189.

Here’s Antar (on the left) looking at my friend Jon Christofersen’s drone composition on the deck of our ship.

The Shot

Often, landscape photography is a leisurely pursuit with cameras mounted on tripods waiting for just the right light to take a picture. Not so on a boat! As we cruised by various features, we had to be prepared to quickly capture an image.

That was the case as we cruised past Grupo La Paz on our April trip to Patagonia. Out of three passes, this pass by appealed to me the most because of the weather. Something about the sky and the light brought a smile to my face as we motored by.

After quickly attaching my telephoto lens, I took a variety of compositions at 200mm. After that, it was time to get out of the rain below deck and enjoy a hot cup of coffee.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

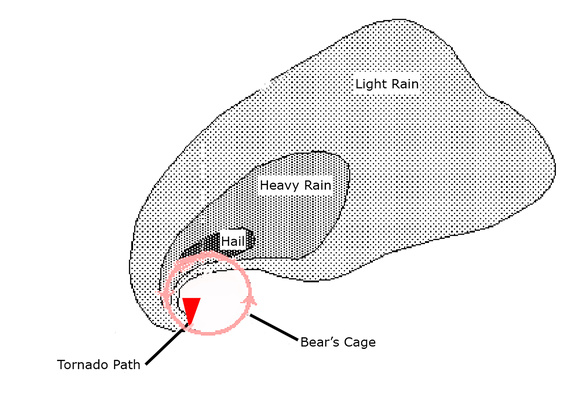

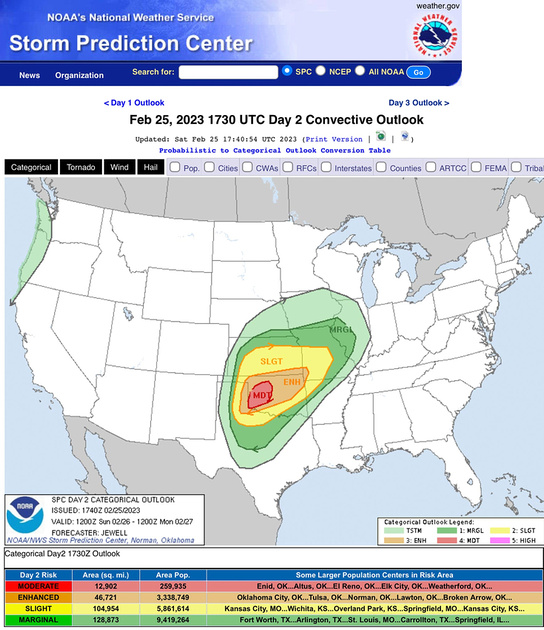

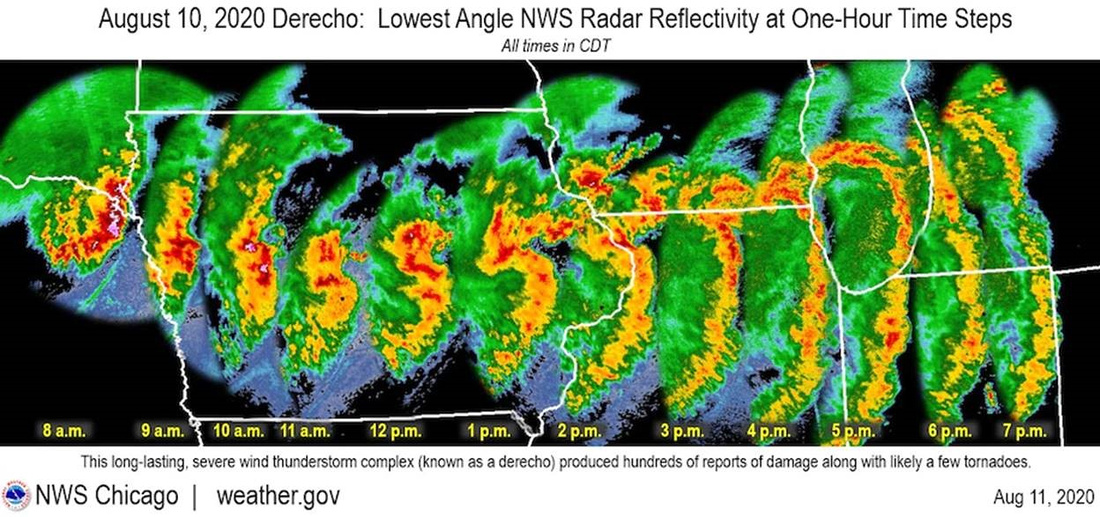

I’m not talking about visiting the zoo. The bear’s cage is a slang term used by tornado chasers. The bear is the danger of a tornado, and the cage is the area where it forms.

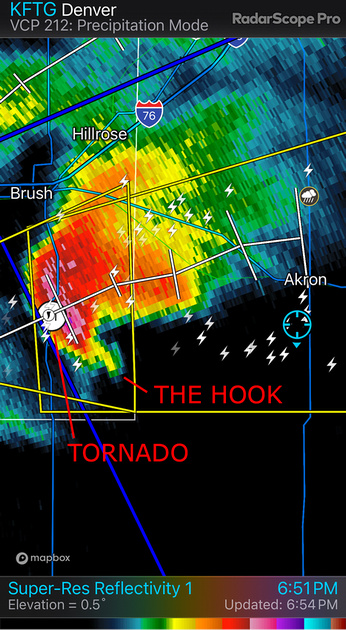

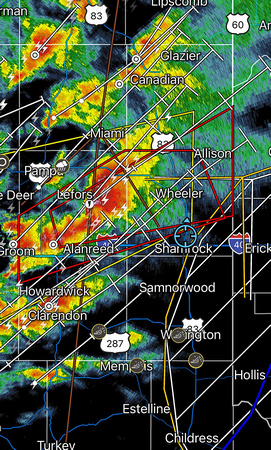

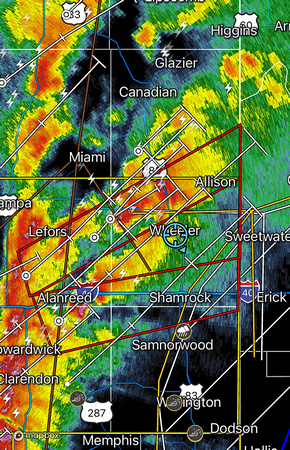

The cage is located beneath a rotating supercell wrapped in heavy precipitation (rain or hail). It often coincides with the characteristic radar hook-echo signature of potential tornadoes. Visibility in the cage is often poor, and the bear can appear without warning.

From www.flame.org

An example of a radar hook-echo signature and a tornado. I’m a safe distance away in the blue circled location.

May 21st

The National Weather Service predicted severe, dangerous storms in southwest Iowa. We drove there in the morning to be in position.

The prediction was spot on. By the early afternoon, intense storms started forming. Soon afterwards, intensifying low level winds added the last component needed to produce tornadoes. We ended up spotting four tornadoes.

Number one was near Red Oak, Iowa. It formed a nice stovepipe that lasted several minutes.

The Red Oak, Iowa tornado.

We moved to a new location to observe another supercell with tornadic potential. Since tornadoes move northeast, setting up south of the expected path is the safest place to be.

We didn’t have to wait long. A supercell approached our position at 60 mph. As it sped towards us, a big bowl-shaped tornado dropped that was wrapped in violently rotating curtains of rain.

The bear’s cage started hitting a tree line a little over a mile away when we realized we were uncomfortably close. We jumped into the van and drove away to the east at high speed.

Sitting in the rear seat, I turned around and saw the bear’s cage growing larger and closer. After what seemed an eternity (probably only 30 seconds), we pulled away to safety.

Jon Christofersen filmed a hyperlapse video of the tornado’s approach. You can view it at https://cderus.zenfolio.com/p476844829/h1bacd4b5#h1bacd4b5.

Tornado number three was a large, destructive multi-vortex tornado. We watched it roar across the road a mile or so east of us. It struck the communities of Villisca, Nodaway, Brooks, Corning, and Greenfield, killing 5 people and injuring 35 others.

An iPhone shot out the front window of the early phase of the deadly Greenfield tornado.

That tornado was rated as a high-end EF4 with ground wind speeds estimated at 185 mph. Wind speeds of 308–319 mph at 36–38 yards above the surface made it the third strongest winds ever recorded in a tornado.

The peak width was 1,600 yards. It stayed on the ground for nearly 43 miles during its 48-minute existence.

We briefly saw our last tornado, number four, as we drove north to get ahead of the storm. But a storm core with huge hail and blinding rain blocked us from continuing the chase. We called it a day.

It was an exhilarating, yet intensely sad day. A four-tornado day is remarkable. But lives were lost, people were injured, and homes and businesses were destroyed.

The Shot

This image of tornado number two was taken a few seconds before we bugged out. From now on, the only bear’s cage I want to see up close is at Brookfield Zoo.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

The South American Lenga tree is a survivor. It’s a deciduous tree or shrub native to the southern Andes range. It grows in areas with low temperatures down to −22 °F and abundant snow.

The northern half of its distribution is only in the Andes. It’s found at sea level in its southernmost natural environment. It can even survive in Tierra del Fuego, the southern tip of the New World.

The Lenga can reach heights of up to 100 feet with a trunk diameter of 5 feet In more northern regions, it grows only at heights above 3300 feet in the form of a shrub.

The dark green elliptic-shaped leaves are dark green and turn to yellow and reddish tones in autumn. The fruit is a small nut 4–7 mm long.

When shaped by the howling winds and icy temperatures of Patagonia, it can take on a bonsai appearance. That archetypal appearance makes it a distinctive foreground for photographs of Patagonia.

A bonsai shaped Lenga tree in a rainbow looming over our Zodiac as we return to our boat in the Patagonian fjords.

The Shot

This is another image of the same area as the waterfall described in my June 7 Land of Giants Friday Photo. If you look closely, you can see the falls in the lower left.

After the falls image, I flew a second drone flight up the glacial stream and higher up. This time, I was looking to include a foreground Lenga tree.

The shape of Lenga in the lower right seemed to complement the diagonal of the stream leading to the glacier. And the trees were starting to turn color (April is fall in South America) adding a pop of yellow to the scene.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Fjord and sound. Both words evoke visions of valleys formed by soaring ice-covered peaks reflecting in deep blue, placid waters far below. They are magical places.

But is there a difference between a fjord and a sound? Thanks to the Vikings, the answer is yes.

Fjord comes from the Old Norse word fjǫrthr meaning “to travel across.” Sound stems from the Old Norse word sund meaning “swimming” or “strait.”

A fjord is an underwater valley carved by glaciers. U- and V-shaped valleys carved by ancient glaciers left steep-sided mountains on either side. After the glaciers retreated, sea levels rose by as much as 390 feet inundating the carved valleys with sea water.

The Patagonian Ice Sheet during the last Ice Age. From antarcticglaciers.org:

A sound is a long, wide inlet of the sea between two peninsulas or other landforms. They are usually wider than a fjord. These underwater valleys are formed by river valley flooding, not by glaciers. Sounds often parallel the coastline, separating it from an island.

Both are often mistakenly used interchangeably. Milford Sound in New Zealand is technically a fjord, and Limfjord in Denmark is actually a sound!

My Visit

The most exciting part of my April visit to Patagonia was experiencing the Chilean fjords. We departed from Puerto Natales and went into the Canal de las Montañas.

From Wikipedia.

Unexpectedly, the seemingly ever-present howling winds and overcast skies of the fjords gave way to a pair of sunny, calm days. We could fly our drones!

The Shot

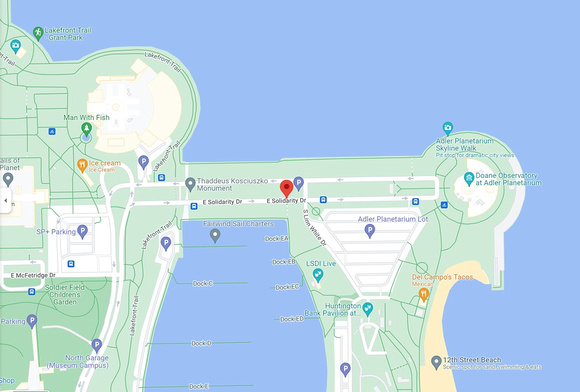

On April 15, we motored to the Bernal Glacier, a 30,000-year-old glacier slowly inching into the Canal de las Montañas. It was tricky flying because drones require line of sight to control them. Our foreground was on the very edge of our ability to maintain radio contact and control them.

The foreground was about three miles away at an altitude of 2,300 feet. Once I flew there, it was a matter of fine tuning the drone’s location. I wanted the glacial cracks aligned with the Cordillera Sarmiento Mountains about four miles further away.

The locations of the boat, Bernal Glacier, drone, and Cordillera Sarmiento Mountains.

Later that evening, Pim, the ship’s cook, poured Chivas on the rocks after dinner. But it wasn’t ordinary ice; these were 30,000-year-old ice cubes from the glacier.

You never know what you’ll experience when you travel!

The next Friday Photo is July 12 due to a family vacation.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

It’s the result of ice. Lots and lots of ice.

The million-acre Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) was formed by glaciers that scraped and gouged the rock of far northeastern Minnesota. The last Ice Age’s alternating episodes of glacial advance and retreat encompassed the period c. 115,000 – c. 11,700 years ago.

When it finally ended, their passage left behind rugged cliffs, crags, canyons, gentle hills, towering rock formations, rocky shores, sandy beaches and several thousand lakes, streams, and islands all surrounded by forest.

The BWCAW extends nearly 150 miles along the international boundary between Canada and the United States. North of the border is Canada’s Quetico Provincial Park while Voyageurs National Park is to the West in the U.S.

The BWCAW offers priceless solitude, challenge and absorption into nature. You won’t see motorized vehicles or many people on its more than 1,200 miles of canoe routes, 12 hiking trails, and over 2,000 designated campsites. You will see black bears, moose, foxes, and deer. And if you drop a line in the water, you’ll be rewarded with trout, walleye, bass, pike, muskie, and panfish.

The area was set aside in 1926 to preserve its primitive character. It became a part of the National Wilderness Preservation System in 1964 allowing visitors to canoe, portage and camp in the spirit of the French Voyageurs of 200 years ago.

My Visits

I’ve been fortunate to spend time in the BWCAW on several occasions. My first trip was during medical school. Eight of us from our Nu Sigma Nu medical fraternity set off during summer break.

That’s me on the far left.

Back then, we either portaged a double pack or a canoe and a single pack. On my last trip there thirty years ago with my son, I was down to a single pack or the canoe.

My medical school roommate Jeff Knutson shows off what a 25-year-old can portage.

Luckily, there’s always down time between canoeing and portaging. For some it’s a book. For others it is sitting down and enjoying the view. I always enjoyed the chance to fish.

Waiting for a bite (fish, not mosquito).

The Shot

Last August I was with Jon Christofersen and several other photographers on a workshop photographing the Milky Way. We stayed in Grand Marais, Minnesota and drove north along the Gunflint Trail Road near the BWCAW every evening for photography.

I wish I could tell you that the red canoe just happened to be at Swamper Lake. But our group leader had brought it along as a prop with this type of image in mind. The scene brought back memories of past serene BWCAW evenings with friends and family.

Since the sky was nearly empty of clouds, I decided to wait for the sun to kiss the horizon. The resulting sun star helped add visual interest to the photo.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

No, it’s not a typo. This title is for my good friend and fellow punster since seventh grade, Mark Hendrickson.

Look at the prominent pouch-like clouds on the left underneath the anvil cloud. Those are mammatus.

Most clouds form in rising air. But not mammatus clouds. They are a rare example of upside-down clouds formed by sinking air.

Mammatus clouds require three ingredients. The first is that the sinking air must be cooler than the air around it. The second is that the sinking air has a high liquid water or ice content. The third is the presence of dry air beneath the moist air.

As the cooler, water/ice-rich air sinks, bag-like cloud sacs form that resemble cows’ udders. The name comes from the Latin mamma meaning udder. Although mammatus most frequently form on the underside of a cumulonimbus cloud, they can develop underneath cirrocumulus, altostratus, altocumulus, and stratocumulus.

Mammatus clouds last longer if the sinking air contains large water drops or large snow crystals. The larger the particle, the more energy and time it takes for evaporation to occur. But the cloud droplets eventually evaporate and the mammatus clouds dissipate.

Mammatus clouds are most often associated with anvil clouds and severe thunderstorms. While they look scary, they are not a warning sign of an impending tornado.

The Shot

On May 19, our storm chasing tour was positioned near Arnett, Oklahoma. The leader picked this supercell as having tornadic potential. But it was a high precipitation supercell that hid any tornadoes inside a torrential downpour.

During our several hour chase, we noticed crepuscular rays (sun beams or God rays) in the distance. We had to stop for photos because an interesting atmosphere is irresistible to photographers.

All we had for a foreground was a barbed wire fence. You’re probably thinking “Couldn’t Chuck find a more interesting foreground?” Please feel free to visit rural Oklahoma and discover a more interesting foreground for my next photo there. 😊

I was struck by the combination of beautiful mammatus above, sun beams in the distance, and the dichotomy between the ominous, dark supercell on the right and the sun peeking out on the left.

We all took a moment from our photography to simply admire the view. The quotation from Cheryl Strayed in her book Wild came to mind. “There’s always a sunrise and always a sunset and it’s up to you to choose to be there for it… Put yourself in the way of beauty.”

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Travelers often perpetuate myths. In 1520, The explorer Magellan used the term Patagón (possibly meaning bigfoot) to describe “giants” living in the southern tip of South America. By his and other accounts, they exceeded at least double normal human height.

Early maps of the New World would sometimes attach the label Regio Gigantum (region of giants) to the area. It’s likely the native Tehuelche, who tended to be taller than Europeans of the time, were the origin of this myth. Tales of giants maintained a hold upon European imagination for nearly 300 years.

The name Patagonia (land of giants) for the region stuck. The region encompasses the southern end of South America.

Patagonia is shaded orange. From Wikipedia.

In the west, it encompasses the southern section of the Andes Mountains along with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and glaciers. In the east, it contains deserts, tablelands, and steppes. With so many features, it’s a photographer’s paradise.

What’s a Fjord?

A fjord is a long, deep, narrow body of water that reaches far inland. Fjords are often set in U-shaped valleys with steep walls of rock on either side.

To be named a fjord, it must be created by glaciers. During the last ice age, glaciers covered just about everything. The movement of glaciers below sea level carved deep valleys. As the ice age ended, these valleys, sometimes thousands of feet deep, were filled with sea water creating fjords.

Fjords are found mainly in Chile’s Patagonia, Norway, New Zealand, Canada, Greenland, and Alaska. Their size can be mind boggling. Sognefjorden, a fjord in Norway, is almost 100 miles long.

The Shot

My trip to Patagonia in April included four days on a boat in the remote Patagonian fjords. We departed from Puerto Natales and were blessed with two days of mild weather, an unusual occurrence in this region.

Our vessel the Explorador

Our drones turned out to be extremely useful. While beautiful from a distance, the interesting features like glacial streams and waterfalls were inaccessible due to nearly impenetrable forest and grueling climbs.

That tiny stream in the valley looks photogenic but is impossible to reach by foot.

Thanks to my drone, I was able to fly upstream and identify several interesting compositions. After taking this image, I flew to an altitude of 3,000 feet and discovered a gorgeous alpine lake over a mile away.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

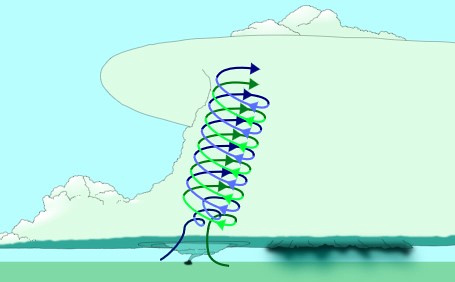

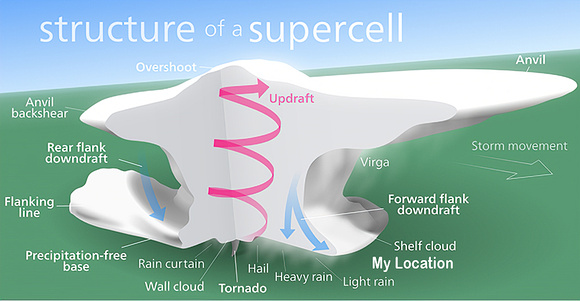

Super isn’t an exaggeration. Supercell thunderstorms can tower over the land reaching heights of up to 13 miles. The anvil shaped top can stretch as large as 60 by 180 miles.

May 23, 2016, near Northfield, Texas

Typically no more than twelve miles across at the base, supercells produce severe weather, including damaging winds over 70 mph, very large hail (the record is eight inches in diameter), and sometimes tornadoes. Once formed, they can last for hours.

The difference between a regular thunderstorm and a supercell is the presence of a deep and persistent rotating updraft called a mesocyclone. This rotation produces a stacked plates appearance as seen above.

An Ingredient List

You need four ingredients for a supercell: wind shear, lift, instability, and moisture.

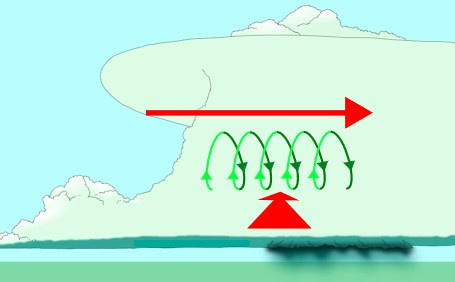

Wind shear is produced by a difference in the speed and direction of wind at different altitudes, typically at 5,000 feet and 20,000 feet. Shear creates rotation of the storm’s updraft, the critical ingredient for supercells.

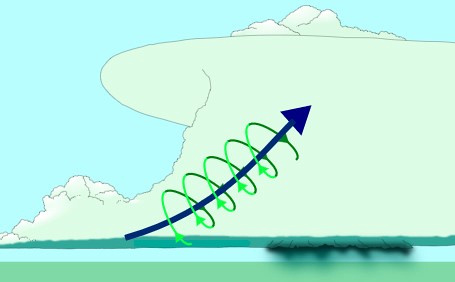

Wind shear also causes the rotating updraft to tilt. That tilt separates the rotating mesocyclone updraft (red up arrow) of warm, moist air from the downdraft (blue down arrow) of rainy, cold air. Without tilt, cold and warm air mix, ending the storm.

From the University of Arizona

Supercells are most common in the central United States. The Great Plains of the Dakotas, Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas offer unobstructed views of these beasts.

The Shot

On May 19, our storm chasing tour was positioned near Arnett, Oklahoma. The leader picked this supercell as having tornadic potential. But it was a high precipitation supercell that hid any tornadoes inside a torrential downpour.

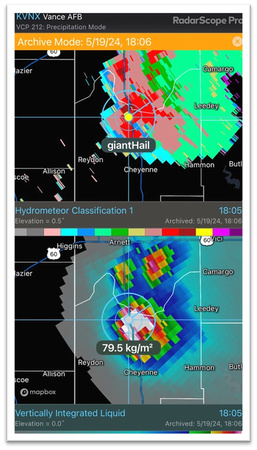

There probably was an unseen tornado hidden in the rain. On radar, the circled area in blue indicates a small debris cloud associated with a tornado. And the second radar image indicates giant hail.

Radar images courtesy of Greg Dutra, ABC 7 Chicago meteorologist and neighbor.

We weren’t disappointed by the lack of a visible tornado. The supercell’s beautiful structure was much more photogenic than a tornado.

After admiring the storm for about a half hour, we returned to the van and chased it until sunset. Then it was time for the long drive to Salina, Kansas, five hours away. After 944 miles of riding in the van that day, crawling into bed at 2:00 am never felt so good.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

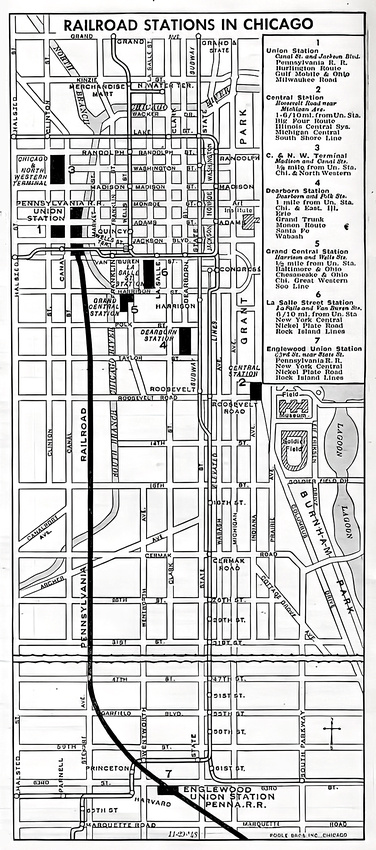

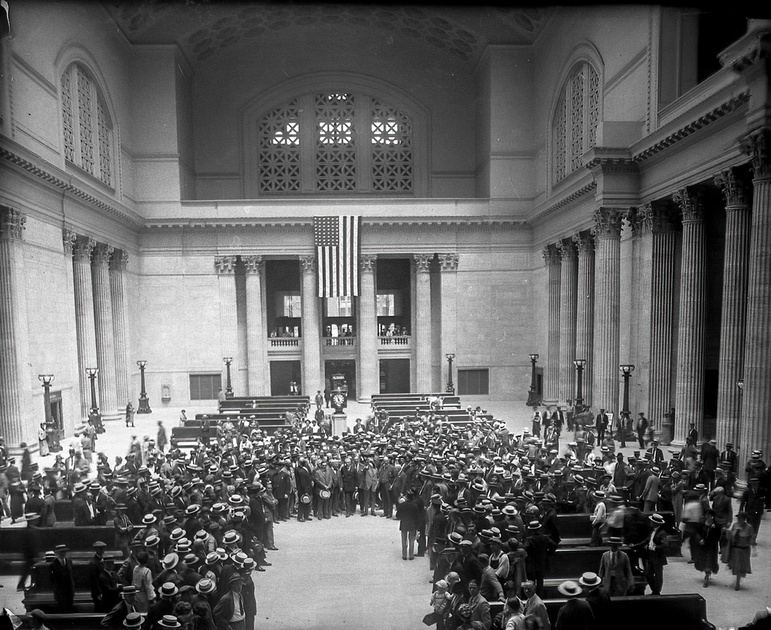

Very few buildings survived the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Old St. Pat’s Catholic Church is one of them. The fire missed the church by a mere two blocks. It became the oldest public building in the City of Chicago.

Irish immigration to Chicago began in the 1830s. Arrivals grew exponentially following serial potato crop failures beginning in 1845. By 1860, Chicago had the fourth largest Irish community in the country.

The same religious divisions in Ireland traveled to America along with the immigrants. Protestants separated themselves from Catholics by both religious identity and by socioeconomic class.

Irishness in Chicago became synonymous with Catholic, working-class, and poor. Prejudice against Irish immigrants led to pervasive social stereotyping. It wasn’t until 1997 that the Chicago City Council exonerated Mrs. O’Leary and her cow of all guilt for starting the Great Chicago Fire.

Chicago’s Irish Catholic immigrants needed their own church. Irish bishop William Quarter met that need by founding Old St. Patrick’s Church on Easter morning of 1846. Named for the patron saint of Ireland, it was the first English-speaking Roman Catholic church in Chicago.

A humble wooden building at the intersection of Randolph and Desplaines Streets served the parish for ten years. A larger replacement was needed, and two of Chicago’s earliest practicing architects, Augustus Bauer and Asher Carter designed the current church.

The cornerstone was laid for the new building on May 23, 1853. It was constructed of yellow Cream City brick from Milwaukee. After three and a half years of work, the current Old St. Pat’s was dedicated on Christmas Day 1856.

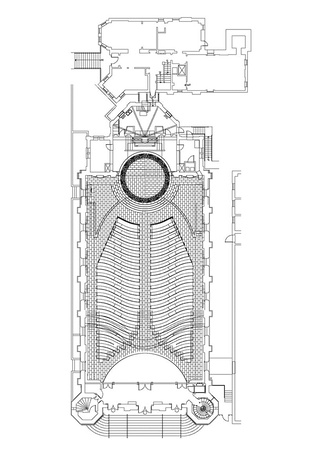

Most Catholic churches feature a prominent crucifix. But not Old St. Pat’s. Look at the floor plan.

The center aisle and the steps to the altar create a cross. And the curving, tapering pews represent the ribs of Christ on the cross. Take another look at the photo.

The center aisle and the steps to the altar create a cross. And the curving, tapering pews represent the ribs of Christ on the cross. Take another look at the photo.

A New Life

Old St. Pat’s was never located in a fashionable residential neighborhood. By 1912 the church, located at Adams and Desplaines Streets, was surrounded by a skid row, manufacturing buildings, and warehouses.

Most churches in this situation would have been abandoned. But in Chicago, the Catholic connection to sacred spaces defies economics.

Thomas A. O’Shaughnessy, an illustrator for the Chicago Daily News, breathed new life into the city’s oldest public building. He was hired to redecorate the church between 1912 and 1922. His legacy includes stunning, luminous windows of opalescent pastel colored stained glass as well as intricate Celtic stenciling on the walls and ceiling.

The inspiration for O’Shaughnessy’s Celtic design elements came from two sources. The first was the Celtic design on display at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The second was a European trip between 1905 and 1906. While in Ireland, he was drawn to the themes and pattern work in the Book of Kells, a 9th-century illuminated manuscript containing the four books of the Christian gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John).

O’Shaughnessy designed, constructed, and personally installed the beautiful stained-glass windows of Old St. Pat’s between 1912 and 1922. The twelve side windows were inspired by the Celtic designs of Ireland’s Book of Kells.

Three windows are a triptych installed in the balcony of the eastern facade of the church. They are known as “Faith, Hope & Charity” and as the Terrence MacSwiney Memorial Triptych. MacSwiney was an Irish playwright, author, and politician. He served as the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork during the Irish War of Independence in 1920.

O’Shaughnessy personally cut and fit over a quarter million pieces of glass into the lead frames of the MacSwiney Memorial Triptych.

The middle MacSwiney window.

The middle MacSwiney window.

Hard Times

By 1950, Old St. Pat’s was again declining and in danger of demolition. Construction of an expressway split the neighborhood causing parishioners to leave for the suburbs.

Fortunately, Old St. Pat’s was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 avoiding the loss of this architectural gem. But the decline in parishioners continued.

By 1983, there were only four registered members of the church. Reverend John J. Wall became the pastor. He created a “church for the marketplace” plan with strong outreach to young adults. He also launched the Center for Work and Faith, to attract working professionals. In addition, he recruited young adults in local bars.

And in 1985, his first Old St. Pat’s “World’s Largest Block Party” drew 5,000 people to Des Plaines Street. The event helped create financial security for the parish.

The four tactics worked. Just two years later, the church’s mailing list had grown to 10,000 people.

The block party ended its run in 2020. But today, Old St. Patrick’s is home to more than 3,000 households and innumerable friends. The future appears bright.

The Shot

When I went to the balcony for a photo of the MacSwiney Memorial Triptych, I noticed the sweeping view of the church below me. This view seemed to capture the spirit and magnificence of this sacred space.

I’ll be gone next week photographing, so the next Friday Photo will be May 31.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

“There Is Peace Even in The Storm.”

“There Is Peace Even in The Storm.”

Vincent van Gogh

A rainstorm usually causes disappointment. Your carefully planned picnic is either postponed or cancelled. And if you’re outside, chances are you’ll be soaked.

But for landscape photographers, it represents an intoxicating opportunity! An approaching storm inspires excitement, peace, fear, and caution, all of which are useful in storm photography.

Today’s Friday Photo epitomizes the photographic rewards of storm chasing. One year ago, I was nearing the end of a six-day chase. There were no supercells that day and no possibility of tornadoes.

But a gorgeous shelf cloud was approaching our location at sunset. A shelf cloud is a low, horizontal, wedge-shaped cloud attached to the base of a thunderstorm. Rising air motion can often be seen in the leading part of the shelf cloud. The underside can often appear turbulent, and wind torn.

This shelf cloud was a beauty, featuring several striations. As the sun approached the horizon, a brilliant, yellow glow suffused the western horizon. And the thick shelf cloud blocked the light causing the eastern horizon to become almost as dark blue as late twilight.

An amazing sense of peace and excitement washed over the group.

The Shot

A cold gust front hit us as soon as we exited the van to set up our tripods. After feeling hot and sweaty all day in short sleeves and pants, we frantically donned our jackets to stay warm.

After taking a few shots looking south, I turned around to see the light show to the north. Wow! As the violent squall line approached us, fear and caution began to permeate the group.

After a few more minutes of wary shooting, we hastily retreated to the van and drove away to escape its approaching fury.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

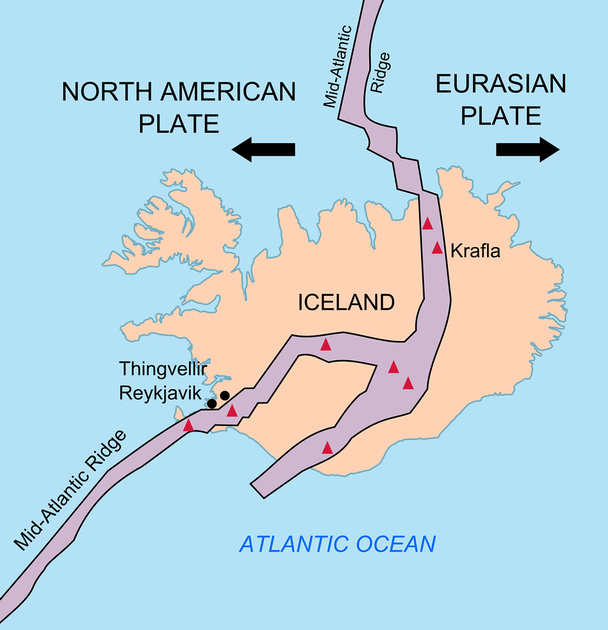

I like using uncommon words. And what could be more fun than working the word jökulhlaup into a conversation?

Jökulhlaup (pronounced jok-ulh-laup) is an Icelandic word. It combines jökull (glacier) and hlaup (running and flood).

Glacial meltwater can be trapped by an ice dam or against a glacial ice sheet. The meltwater can be caused by warm temperatures or by volcanic/geothermal heating.

The word was first used in the 1800s to describe the well-known subglacial outburst floods from Vatnajökull, Iceland’s glacial icecap. Nowadays, any large and abrupt release of glacial water is referred to as a Jökulhlaup across the world.

On my Alaska photo trip in February, we stayed in the town of Sutton. One of the highlights of the trip was an open-door helicopter ride to photograph an ice cave.

It was a chilly, but exciting ride to the ice cave!

The cave was formed by a jökulhlaup. A one-hundred-foot-deep glacial lake had been very slowly draining out of a small crack at the base of the ice. Over time, the crack widened and then reached a critical size.

The trickle suddenly transformed into a torrential flood, carving out this remarkable cave. We were able to explore several hundred feet into it. Being bathed in blue light and covered by millions of tons of ice is an eerie and thrilling sensation!

The Shot

I’ve made three attempts to photograph an ice cave. The first time, in Iceland, the cave was very short. I also failed to photograph into the light with a person near the entrance to provide scale.

The second time was during my summer of 2022 Alaska trip. Thick fog and rain forced our helicopter pilot to abort his attempt to land at the ice cave.

My third time was the charm. Helicopter access was easy, and I was determined not to repeat my prior compositional mistakes.

I’m trying to imagine how much water gushed out of the glacier to melt this passage!

There were several locations with good leading lines to the opening and silhouetted model. This one was the most pleasing. I was also hoping viewers could “step into” my shoes and feel the same excitement I was having.

I also captured a 2 minute, 45 second video walking through part of the ice cave. If you’re interested, it’s on my Zenfolio website at Zenfolio | Chuck Derus | Alaska.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

One more class would fill my schedule. It was spring quarter of my freshman year in college. There weren’t many courses open because my alphabetical group was the last to choose.

South American Geography 101 was still open and seemed better than the alternatives. Little did I know my selection would ignite a lifelong passion to visit the continent based on my professor’s mesmerizing photographs.

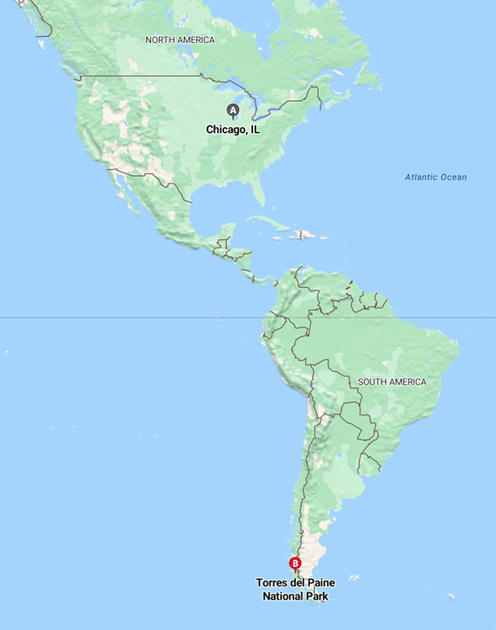

My dream finally came true in 2014 when I visited Chile and Argentina. I photographed Patagonia’s Torres del Paine (PIE-neh) national park. Torres is the Spanish word for tower and Paine means blue in the native Tehuelche language. I also photographed Fitz Roy.

TripAdvisor elected the park as the Eighth Wonder of the World, and it deserves the honor. Established in 1957, it encompasses breathtaking Andean mountains, forests, steppes, glaciers, lakes, rivers, and fjords. My youngest daughter and son-in-law visited Patagonia a few years ago and thoroughly enjoyed the experience.

The park averages around 252,000 visitors a year, of which 54% are international. It’s famous for strong winds that peak in summer (November to January in the southern hemisphere). Expect to be blown off your feet on occasion.

Second Chances

Since it’s 6,487 miles from Chicago, I thought it was going to be my one and only visit. But a second chance presented itself!

During the pandemic lockdown, one of my photography workshops was cancelled. Rather than accept a refund, I opted to roll over the deposit for the opportunity to revisit Patagonia in 2024.

I recently returned from that trip. It was just as magical as the first trip, with the added adventure of four days on a boat in the Patagonian fjords.

Before departing, I wondered if my photography skills had improved over the decade. Was Maya Angelou correct? “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.”

The Shot

Lake Pehoé (hidden lake in Tehuelche) provides the iconic view of Paine Grande (left) and the Cuernos (horn) del Paine (right). Photographing well before sunrise was the key change from a decade earlier.

Thirty to forty-five minutes before sunrise, reflected sunlight from below the horizon bathes the landscape in beautiful soft light without any harsh, distracting shadows. It appears to be sunrise, but with much more pleasing light.

Packed up and leaving as a hoard of photographers arrives after the best light is over.

By the time the sun started touching the top of the peaks a half hour later, the site was overrun by photographers. The direct light started producing harsh shadows and dull colors. It was time to pack up and began my 52-hour journey back to Chicago.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

We’re surrounded by beauty. But sometimes, the camera fails to capture that arresting scene. Our eyes see the world differently than the camera.

For example, walking through a forest is an alluring experience. Tree trunks, branches, and leaves dance in the light, combining to form lovely images that change with every step.

But what happens when you stop walking and take a picture of the forest? Oftentimes, the photograph is disappointing. The grandeur has been reduced to a chaotic, confusing, jumble of elements by the camera.

I once spent two days in the Hoh Rainforest in Washington State. The sights were mesmerizing. But I emerged with only one good photograph. The hundreds of others appeared to be a feeble attempt to document an explosion in a green spaghetti factory!

Other times, beauty is inescapable, even to the camera. For example, you can stand anywhere on the breathtaking Zabriskie Point Overlook in Death Valley National Park and take the same pleasing image of Manly Beacon.

What About Ugly?

You might think that “ugly” subjects never make arresting photographs. For example, who gets excited at the prospect of images of mud?

Yet images of mud can be delightful.

Mud cracks in Death Valley National Park

The Shot

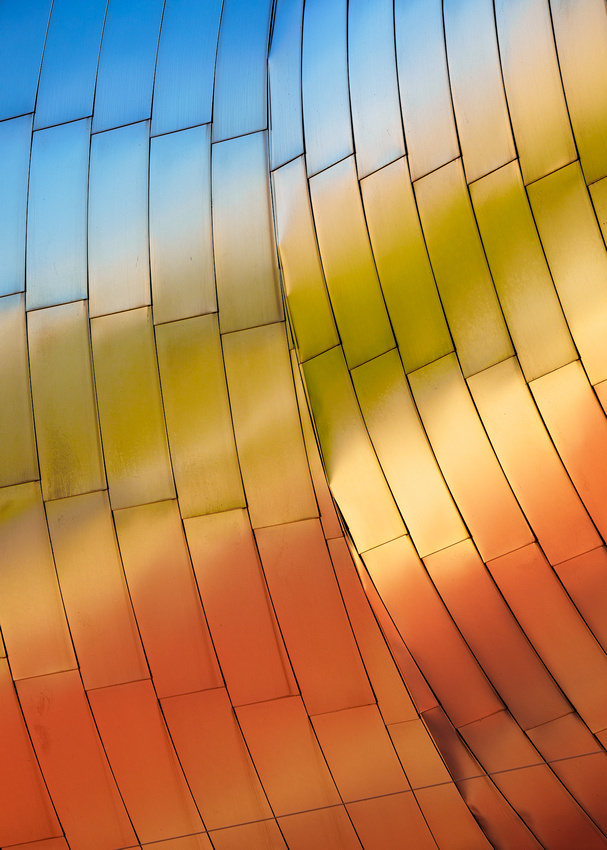

Two years ago, I spent several days on Florida beaches photographing the simple beauty of waves. But one evening, the wind was calm, and no good waves appeared.

I could have given up and left for dinner. But I decided to seek out an alternative subject instead.

An assemblage of rusty steel H-beams and broken concrete block was just down the beach. Most people would classify it as junk and want it removed. Could ugly be transformed by the camera?

It had potential. First, I looked for an angle to capture the diagonals. Next, I carefully positioned the camera to avoid any distracting overlapping of the beams. Finally, I used a long shutter speed to simplify and smooth out the water, further reducing distractions.

The sunset light warmed up parts of the rusty orange beams, contrasting nicely with the blues of the sky and ocean. Everything just seemed to come together beautifully in this satisfying image.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

The Cones fuse beauty and grandeur to create a breathtaking amalgam. Granite peaks soar majestically to the heavens, adorned with ragged ridges, sharp spires, and towering cliffs. Most of these peaks have never been climbed because of the rugged terrain, technical difficulties, and limited access.

The Cones are situated near Haldi village in the Ghanche district of Gilgit Baltistan in Pakistan. The landscape surrounding Haldi village is mesmerizing, Verdant valleys, glistening streams, and snow-capped peaks create an idyllic setting.

Along with the captivating Cones, the area offers other attractions. The Saling Valley, Yochung Valley, Machulu Valley, and Haldi Village itself are exceptional sightseeing locations. However, the Machulu Village viewpoint truly shines among these options.

The Haldi Cones from Machulu Village

Working the Area

As usual, we arrived early on the morning of November 4 and scouted for locations along the stream running through Haldi village. The villagers were curious and several of them struck up conversations with our group of photographers.

We kept crisscrossing a stream evaluating compositions leading to the Cones. In some spots, it was tricky crossing the rocky stream. Only a single footbridge graced the stream. And in Pakistan, bridges are shared by people, vehicles, and livestock.

This goat thought the better of it and turned around when he spotted friend and fellow photographer Jon Christofersen starting to cross.

The Shot

After finding a composition, we waited for the light. If the sun was too low, the mountain would be unappealing. And if it was too high, numerous harsh shadows on the mountain and in the valley would be chaotic and distracting.

To play it safe, we took photographs every five minutes or so for about a half hour. After that, it was back to town for breakfast and a warm cup of coffee.

I’ll be in the field for the next two weeks, so the next Friday Photo will be on April 19.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Picturesque is the word to describe northern Pakistan. And the Saling Valley is filled with vivid images.

Nestled in the Ghanche District of Khaplu in Gilgit-Baltistan, the Valley is a destination waiting to be discovered. It also serves as a gateway to the enchanting Hushe Valley.

The markhor goat is the national animal of Pakistan and is abundantly present in the Valley. The word mārkhor (مارخور), meaning "snake-eater," comes from both Pashto and classical Persian languages. It stems from the snake-like form of the male markhor's horns, possibly leading ancient peoples to associate them with snakes.

From science.org

Most people in the Valley grow wheat, potatoes, tomatoes, and other vegetables. Small herds of livestock add milk and meat to the diet. We found everyone to be hospitable and friendly.

The Shot

We awoke well before dawn in nearby Khaplu on November 3 and then drove east. After a short while, we turned north on a connecting road to the town of Saling. Before we reached town, we stopped, parked, and hiked about a mile east looking for a foreground to complement the distant mountains.

The pre-dawn light beautifully embraced the distant peaks. We had colorful bushes in the foreground and a pair of trees created a complimentary frame-within-a-frame for our composition. Once the sun came up, harsh shadow lines created so many distracting shadows that we put away our cameras.

After that, it was a short hike back to our vehicles. Luckily, breakfast and a hot cup of coffee was not far away in Khaplu.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Greener Than Green River Soda!

Is it a celebration of Irish heritage or an excuse to party? It’s probably both. Parties, bar crawls, and parades are held worldwide celebrating St. Patrick’s Day.

The history of St. Patrick’s Day in Chicago dates back more than 175 years. Now a longstanding tradition, Chicago’s Irish parade was first held in 1843 becoming an official city event in the 1950s. Along with the downtown festivities, Chicago’s proud Irish heritage is also on full display in multiple neighborhoods.

Since 1962, Chicago has dyed the east branch of the Chicago River neon green in a now iconic annual celebration. Thousands of people line the Riverwalk and crowd Chicago’s bridges to glimpse the phenomenon. It’s typically held at 10 a.m. the Saturday before St. Patrick’s Day and is followed by the downtown parade.

Crews from the Chicago Plumbers Union Local 130 create a spellbinding spectacle spreading the dye from boats in honor of St. Patrick’s Day. The best views of the newly colored river are from Upper Wacker Drive between Columbus and Fairbanks.

iPhone shot from the Michigan Avenue bridge.

The event started thanks to serendipity. In 1961 Stephen Bailey, business manager of the Chicago Plumbers Local 130, was approached by a plumber.

His normally white coveralls were heavily stained (or dyed) the perfect shade of Irish green. When Bailey asked how his coveralls got this way, he learned that the dye used to detect leaks into the river colored the fabric that special color.

That's when Mr. Bailey bellowed, “Call the mayor…we will dye the Chicago River green!” That first 1962 river dyeing turned the waters green for nearly a month. Currently, the color only lasts for a few hours. The union’s environmentally friendly dye formula remains a closely held secret.

The Shot

I had never witnessed the event, so fellow photographer Jon Christofersen and I headed downtown last Saturday. In retrospect, we should have left earlier as the traffic and crowds made for slow going.

After trying in vain to find a place to launch our drones in the Columbus/Fairbanks area, we hiked west to Wolf Point at the convergence of the north, south, and east branches of the Chicago River. It was easy to launch drones from there, but signal interference from the buildings limited our range.

I enjoyed this view the most. After the drone landed, we made our way back to our parked car. I should have brought my regular camera as the St. Patrick’s Day revelers were as colorful as the river!

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

From the ordinary to wild and downright wacky. The variety of ice we encounter in nature depends on the conditions that created it.

Two forms of ice, hoar frost, and rime ice, excite photographers the most because of their photogenic nature.

Hoar Frost

We’re all familiar with dew. When supersaturated moist air near the surface of the ground is cooled to its dew point, tiny droplets of water condense on surfaces.

Hoar frost is formed by a similar process. But with hoar frost, the supersaturated moisture in the air skips the liquid droplet stage and goes straight to ice when temperatures are below freezing. Hoar frost also needs calm air that allows those complex lacy deposits of crystals to form.

The name derives from the old English word “hoary,” meaning getting on in age. Many trees, especially evergreens, take on a "hair-like" appearance resembling a white, feathery beard. These deposits are quite fragile.

An example of hoar frost crystals on the icy Dietrich River in Alaska.

Rime Ice

Rime ice can also coat nature in magical ways. When supercooled (below 32°F) fog droplets instantly freeze and attach to exposed surfaces below 32°F, you get rime ice.

Soft rime ice forms under calm wind conditions. The fog usually freezes to the windward side of solid objects, particularly tree branches and wires. It is similar in appearance to hoar frost with narrow white icy needles and scales. Soft rime is quite fragile.

Hard rime ice is denser and more difficult to remove. It’s often seen on trees atop mountains and ridges in winter, when low-hanging clouds cause freezing fog. The fog freezes to the windward side of tree branches, buildings, or any other solid objects, usually with high wind velocities and air temperatures between 28 and 18 °F.

The Shot

We arose on the morning of February 18 and drove the Dalton Highway to an area near Livengood, Alaska looking for a group of hard rime ice-encased trees. We arrived too early and waited in the van where it was warm.

The two trucks that went by both stopped to check on us as we might have been a disabled vehicle. It was a good feeling to know that people cared about our welfare in that remote stretch of Alaska.

As dawn approached, we wandered through the knee-deep snow looking for compositions. This composition was framed on top by a bowed-over tree and an upright tree. Inside the frame were three rime-encased trees and clouds to the east.

Normally, sunrise shooting is a frantic race against time. You typically have mere minutes to capture the warm colors of dawn. But near the Arctic Circle, we had close to an hour of good light! After two hours of photography, we headed back to the van for the long drive south to Sutton, Alaska.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

What a name! Coldfoot, Alaska (population 34) is aptly named. The lowest unofficial recorded temperature there was a chilly -82 degrees Fahrenheit!

The town began as an 1899 gold mining camp named Slate Creek. Folklore has it that the current name was derived from gold rush prospectors getting "cold feet" about making the 240-mile journey further north to Deadhorse.

The town languished until the 1970s when the Alaska Pipeline was built. Now it’s a rest stop on the Dalton Highway for ice road truckers heading to the oil fields on Alaska’s northern coast.

The town consists of a truck stop, a motley collection of old-school gas pumps, a hotel, a trooper’s office, an Alaskan Department of Transportation office, post office, and a runway for bush planes.

The Coldfoot Camp truck stop was founded by Iditarod champion Dick Mackey. He started his operation selling burgers out of a converted school bus. Truckers then helped build the truck stop and cafe.

The Coldfoot Camp Trucker’s Café menu.

The hotel rooms are spartan former pipeline worker trailers. But the hotel is the best (and only) hotel in town, so I paid the $300 per night price and enjoyed the experience!

The hotel.

Heat, hot water, a shower, and electricity!

The Shot

Our photography group left Coldfoot on the evening of February 16 in search of the Aurora Borealis. After driving about an hour North, we stopped at the Dietrich River bridge and headed to a location we scouted that afternoon.

But the foreground and the anticipated location of the Aurora didn’t seem quite right. So, we piled into the car and relocated further upriver. We had to trudge about 100 yards in knee deep snow after we stopped at a nearby frozen lake.

Our reward was a pattern of strong leading lines created by tree shadows aimed at a mountain peak across a frozen lake. Now we just had to wait.

Our patience was rewarded when the light show began. We didn’t even notice or care that it was a chilly -11 degrees out. Nature’s beauty mesmerized us. After about three hours, the show stopped, and we headed for the warmth of our unique hotel rooms.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

The morning of January 20 began in a joyous, beautiful, and blessed place. I was at Holy Trinity Polish Catholic Church in the Pulaski Park neighborhood of Chicago. The occasion was a photo tour of this historic church. The tour ended on a somber note.

The church, completed in 1906, is a blend of several architectural styles. This blending is reminiscent of Poland’s Middle Ages churches. As churches sustained damage by war or fire, they were rebuilt and remodeled in a multitude of styles. The architect evidently hoped to remind the Holy Trinity parishioners of churches from the old country.

Christmas decorations in the Polish tradition go up on December 24 and come down February 2nd on Candlemas.

For over a half century, Holy Trinity was the center of activities for its 60,000 parishioners. Everything you could possibly want was available at church or in the square mile that it served. In 1960, when the Kennedy Expressway cut through the heart of Chicago’s Polonia, the neighborhood and parish slowly declined as Poles moved to the suburbs.

Mass is celebrated strictly in the Polish language. In honor of its 100th anniversary, the congregation began a renovation campaign in 2005. Today, the church’s many features are beautifully restored.

Part of the ceiling

Catacombs

During construction, pastor Casimir Sztuczko CSC wanted to set aside an area to venerate the holy relics of saints and the beatified. The result is one of the most distinctive and interesting aspects of Holy Trinity, the so-called Catacombs.

Located in the basement, it consists of a winding path lined with niches containing saintly relics leading up to a chamber containing the grave of Christ. There are now 267 relics in the catacomb.

Part of the Catacombs

The Shot

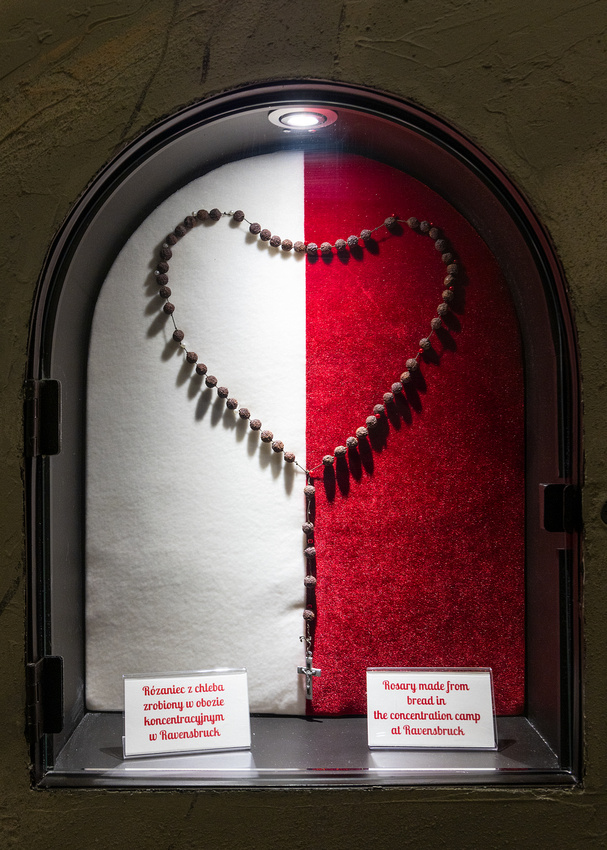

One heart-wrenching relic commanded my attention. I was looking at a rosary made from bits of bread at Germany’s Ravensbrück concentration camp.

Ravensbrück was a Nazi concentration camp in northern Germany exclusively for women from 1939 to 1945. An estimated 132,000 women passed through the camp during the war. Many of them were slaves working under unspeakable conditions for the Siemens & Halske company. Among other things, Siemens produced field telephones of the type "Feldfernsprecher 33."

About 48,500 women were from Poland. Fifteen percent of the prisoners were Jewish, with eighty-five percent from other races and cultures. Almost half of all prisoners died at Ravensbrück. The majority perished from disease, starvation, overwork, and despair. About 2,200 were gassed.

Hoping they might survive; Polish Catholic prisoners made rosaries from their skimpy bread rations and hid them. Discovery meant death. The homemade rosary on display had been soaked in the blood of a Polish mother and daughter killed at Ravensbrück.

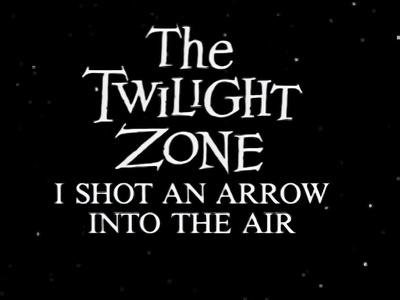

My thoughts were jolted back to the November 10, 1961, episode of The Twilight Zone. In the episode Deaths-Head Revisited about a concentration camp commandant, Rod Serling ended with this powerful outro.

“All the Dachaus must remain standing. The Dachaus, the Belsens, the Buchenwalds, the Auschwitzes; all of them. They must remain standing because they are a monument to a moment in time when some men decided to turn the Earth into a graveyard. Into it they shoveled all their reason, their logic, their knowledge, but worst of all, their conscience. And the moment we forget this, the moment we cease to be haunted by its remembrance, then we become the gravediggers. Something to dwell on and to remember, not only in the Twilight Zone but wherever men walk God's Earth.”

Lest we forget,

Chuck Derus

Last week’s blog was about compositions that use a frame within a frame. This is a second composition framing Ladyfinger using a pair of trees. Let me know if you prefer the horizontal photograph from last week or this week’s vertical composition.

Driving Through Pakistan

We drove every day during our thirteen days in Pakistan’s Hunza Valley. Delays were not uncommon. 😊

Scores of children walking, laughing, and talking while walking to and from school were a ubiquitous sight. There were no parents dropping off their kids at school. Walking several miles up and down thousands of vertical feet was common.

Our expedition leader, Muqeem Baig (Climax Adventure Pakistan | (climaxadventurepk.com)) commented that the literacy rate of Hunza Valley is above 95 percent. And all children have access to a high school education.

A few of the schoolchildren we met in villages walking to and from class.

Government school is only $2 US dollars a month. Private schools are substantially more, up to $200 a month.

The Shot

It was early on the morning of November 7 when we arrived at our Ladyfinger viewpoint. The Peak was about 5.5 miles away in the distance. We had sufficient time to scout several possible compositions.

This composition really seemed to place Ladyfinger in a frame within the two-dimensional frame of my photograph. Ladyfinger is in the left center, with nearby Hunza Peak at 20,570 feet on the right.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Ladyfinger Peak (also known as Bublimotin, Bubli Motin, or Bublimating) is a distinctive rock spire. Located near the city of Gilgit in the westernmost part of Pakistan’s towering Karakoram Mountain range, it stands tall as a lone sentry amidst the gorgeous embrace of the Hunza Valley.

The Peak is a sharp, relatively snowless rock spire that climbs to a dizzying height of 20,000 feet. The last 1,830 feet to the top are nearly vertical.