Welcome to the landscape photography blog by Chuck Derus. Thanks for looking and for your comments!

Lucky Strike

Extra ordinary means very ordinary. But extraordinary is defined as extremely unusual or remarkable.

As photographers, we aim to transform the ordinary into extraordinary. We might employ composition, perspective, lighting, emotion, abstraction, tone, and post-processing to create a compelling image.

You probably envision the Grand Canyon as extraordinary. And it is to the eye.

To the camera, it usually comes across as a dark hole in the ground. It works well for selfies and for “tourist” photos. But if you’re trying to create a compelling landscape image, it’s an extremely difficult location.

The Shot

The extraordinary qualities of storm light came to my rescue two summers ago on a trip to the Grand Canyon. Just as our group pulled into the parking lot of the North Rim Lodge, a monsoon storm appeared.

Forgetting about registration, we raced to the overlook and set up our cameras. A lightning trigger attached to the camera allowed us to capture a bolt much faster than we could possibly react and manually press the shutter button.

Most of the bolts were unremarkable or half in or half out of the frame. But this frame captured a bolt beyond the Zoroaster Temple formation in the distance. And there’s just a hint of a rainbow on the left.

It was a lucky strike that helped bring a bit of extraordinary into this image.

I’ll be on the road next week, so the next Friday Photo is March 21.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

The Karakoram Range

How long is a meter? It’s one ten-millionth of the distance between the equator and the North Pole.

Eight thousand meters may seem like an arbitrary number. But that number looms large for mountain climbers.

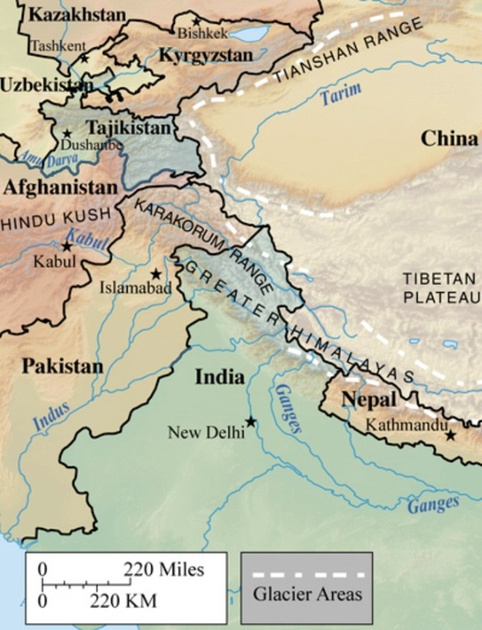

Only 14 mountain peaks on Earth stand taller than 8,000 meters (26,247 feet). And all 14 are found in the Karakoram and Himalayan Mountain Ranges of Central Asia.

The Karakoram boasts the greatest concentration of high mountains in the entire world and the longest glaciers outside of the high latitudes. This monstrous mighty mountain system extends 300 miles along the watershed between Central and South Asia.

The borders of Tajikistan, China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India all converge within the Karakoram Range. It’s pronounced “Kurra-koorrum,” a rendering of the Turkic term for “Black Rock” or “Black Mountain.”

Source: Brittanica

Ultar Sar

The Karakoram Range is a photographer’s dream. It’s the youngest, steepest, and most rugged mountain range on the planet. And there are glaciers galore.

Ultar Sar isn’t one of the highest peaks of the Karakoram. But it dramatically rises 17,388 feet above the Hunza River in only about 5.6 miles of horizontal distance.

By Brian McMorrow https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=768980

In this photograph by Brian McMorrow, Ultar Sar is in the center foreground viewed from the southeast. Shispare is in the center background.

Five glaciers drain the slopes of the massif. They are (clockwise from north): the Ghulkin Glacier, the Gulmit Glacier, the Ahmad Abad Glacier, the Ultar Glacier, and the Hasanabad Glacier.

The Shot

On November 10, 2023, I was with friend Jon Christofersen and our photo group near the town of Ahmad Abad. I launched my drone and flew north up the valley towards the glacier and mountains.

After flying about 6,000 feet north into the valley and climbing 2,600 feet, I arrived at the location marked 25 on the map. It offered a potentially glorious view of the Ahmed Abad Glacier in the foreground with Ultar Sar (about 5 miles away) and possibly Shispare in the distance (about 9 miles away).

But the roiling clouds didn’t cooperate. I held station with my drone for 30 minutes. Only one image showed the Ahmad Abad Glacier and probably Shispare in the distance. Ultar Sar never broke out of the clouds.

Disappointed, I downloaded the images after my trip and never processed them. But I enjoy looking through old “rejects” trying to find and salvage a keeper.

This reject appeared promising. While it didn’t feature both mountains, the combination of the Ahmad Abad Glacier valley with just the peak of Shispare breaking through the clouds in the distance made me happy.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

A Burger and Cones, Please

It’s the second highest paved road in the world. The Pakistani name N-35 doesn’t do it justice. Most call it the Karakoram Highway. And some have dubbed it the Eighth Wonder of the World because of its high altitude and construction difficulties.

This marvel of modern engineering extends 810 grueling miles. The 551 miles in Pakistan begin in the Punjab province of Pakistan. Along the way, it passes through the Karakoram Mountains. The final 257 miles are in China, beginning at the summit of the 15,466-foot-high Khunjerab Pass on the Pakistani/Chinese border.

From Wikipedia

The Cones

The village of Passu is a renowned tourist destination along the Karakoram Highway. It’s situated in the Gojal valley of Upper Hunza in Northern Pakistan, not far from the Chinese border. I was there in November of 2023 with a photography group.

Passu is celebrated for its landscapes and breathtaking views of the 24,534-foot Passu Sar Mountain and the Passu Glacier. But the most photogenic peak in the region is the 20,033-foot Passu Cathedral, also known as the Passu Cones.

A Burger

After a week of mouth-watering curry dishes, our group was looking for some variety. Lo and behold, our guide had just the spot.

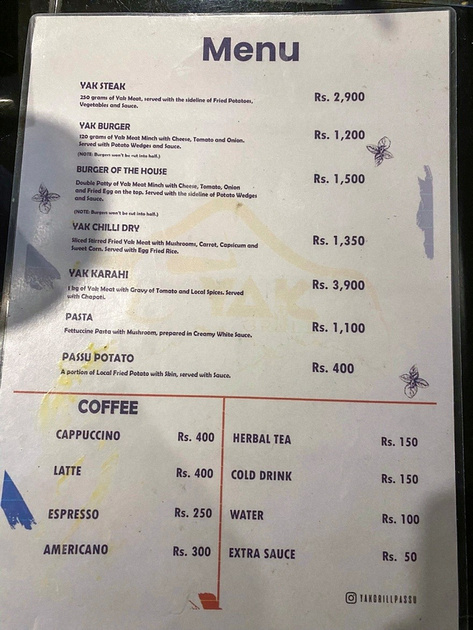

Passu is home to this culinary wonder. If you want to check it out further, the Yak Grill has a Facebook page at (2) yak grill passu - Search Results | Facebook. The menu seemed vaguely familiar, despite being 7,000 miles away from home.

I ordered the Burger of The House and thoroughly enjoyed my meal. It’s the tastiest, juiciest yak burger on a homemade bun I’ve ever had! And the fries are good as well. If you plan on going, $1 US equals around 279 Pakistan Rupees.

The Shot

Our group spent a day photographing around Passu. On a whim, I wandered across the highway from our hotel for an unobstructed view of the Passu Cones. As the snow and clouds swirled around the summit, myriads of pointy peaks appeared and disappeared. Atmosphere!

This image was my best out of numerous attempts that wonderful morning.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

The Journey

Sometimes, it’s only a few steps from the car. A great photograph can be that close. But other locations require a calculation about your hiking prowess.

Most landscape photographers hump a 30-pound backpack full of gear. And I’m not getting any younger. Uphill hikes at elevation can be difficult.

Despite the challenges, hiking to a location is part of the fun. It’s a wonderful time to enjoy being in the wilderness. Occasionally, it’s reassurance that I don’t need a cardiac screening test.

Last October, I joined friends and fellow photographers Steve Horne and Scott Fuller to explore the Southwest. One of our stops was Zion National Park.

I talked about icons in the previous Friday Photo. Canyon Overlook in Zion is one of them. It’s a gateway to one of the most magnificent views in the park.

The Canyon Overlook trail isn’t very long or challenging. It’s just one mile with an elevation gain of only 163 feet. But it offers a breathtaking view.

The trail starts with a set of stairs where most of the elevation gain occurs. From there, it’s relatively easy the rest of the way. You are walking along and below beautiful sandstone walls. While there are sheer drop-offs, many have guardrails.

The trail ultimately emerges onto a hilltop covered with hoodoos (mushroom shaped rocks). It then weaves across the sandstone slickrock and between pinyon pines to reach Canyon Overlook.

East Temple looms to the north, while to the west spreads a panorama highlighted by Bridge Mountain, the West Temple, the Towers of the Virgin and the Streaked Wall.

The Shot

Once there, it was a matter of finding a composition and waiting for the sunrise. The guardrail-protected overlook had a nice view, but we kept exploring. Treading carefully, we went off trail and each of us found slightly better compositions near the edge of the cliff.

Just before dawn, the clouds suffused the landscape with beautiful pinks. Taking our pictures, we packed up for the return trip. On the way, we were delighted to spot a group of desert bighorn sheep, recently reintroduced to Zion.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus

Icons

Some photographers love them, and others avoid them like the plague. There’s probably a mix of emotions in most photographers.

What camera-toting individual could visit Yosemite National Park without going to Tunnel View? Or go to the Grand Tetons without seeking out the Mormon Barn Row?

Icons are icons because they are majestic locations. The views are breathtaking, they are easy to access, and composition is self-evident. But images of them are a dime a dozen.

I wonder if photographers secretly hope for a unique version. With the right light and weather conditions, there’s always a chance for a new and distinctive take on a familiar classic.

But most of the time, if we’re lucky, we leave with something that’s close to what others have accomplished.

Ansel Adams was without peer as a landscape photographer. He defined the genre for those that followed.

My introduction to him was via The Ansel Adams Guide series by John P. Schaeffer. Adams’ image, Tetons and the Snake River, is the defining image of this iconic location.

Tetons and the Snake River by Ansel Adams

The Shot

I was photographing fall color in Grand Tetons National Park last September. The urge to take out my camera at the Snake River overlook where Ansel Adams took his defining 1942 image was overwhelming.

Eighty-two years later, the view was quite different. The trees had grown obscuring the picturesque S-curve leading to the mountains. But part of the river and the magnificent mountains were just as visible.

My image was nothing remarkable, but satisfying, nevertheless.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus