Hail Roar

What’s That Roar?

Last week I was storm chasing on the Great Plains. I went with the Silver Lining Tours (https://www.silverliningtours.com/) photography tour. We traveled almost 3,000 miles of Colorado and Kansas backroads in search of thunderstorm supercells and the tornadoes they sometimes spawn.

You may be wondering if it’s dangerous. Staying safe on my own would have been very chancy. But the tour’s co-owners Roger and Caryn Hill are a formidable meteorological team. Roger earned a spot in the Guinness Book of Records by witnessing over 850 tornadoes.

I felt safe. The real danger is eating fast food for a week. I’ve actually sworn off French fries since I got back.

Back to the Roar

No tornado is present in this photo. There’s a small, barely rotating supercell in the right center with a wall cloud (where tornadoes form) hanging down from it. What appears to be a tornado below the wall cloud is SCUD (strata-cumulus under deck). On the left is a shelf cloud ahead of a new storm.

I never saw a tornado last week. But I heard a sound I had never heard before standing in that field near Winona, Kansas. It was a continuous low rumble like thunder. But it wasn’t thunder because it was occasionally punctuated by the sharp crack of actual thunder. What was it?

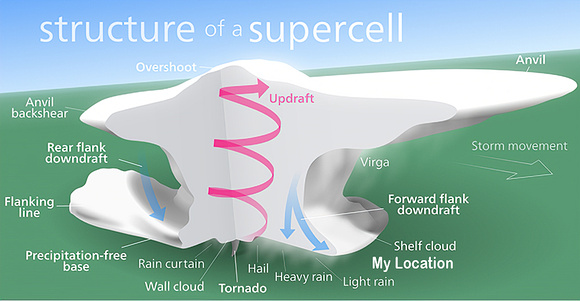

Caryn answered my question. We were standing under the precipitation-free anvil a few miles away from the updraft base in the path of the storm. The hail, heavy rain, and light rain were approaching us.

What I was hearing was hail roar. In the cloud’s updraft, millions and millions of suspended hailstones were colliding. Their collective grinding tens of thousands of feet above us was what I was hearing.

By Vanessa Ezekowitz - Supercell02.jpgMeso-3.PNG, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4446808

Hail

Hail is a form of precipitation consisting of solid ice that forms inside thunderstorm updrafts. Raindrops carried upward by the updrafts into extremely cold areas of the atmosphere then freeze. Hailstones can grow by colliding with liquid water drops that freeze onto the hailstone’s surface.

Hail falls when it becomes too heavy to be suspended by the strength of the thunderstorm’s updraft. Smaller hailstones can be blown away from the updraft by horizontal winds, so larger hail typically falls closer to the updraft than smaller hail.

How fast it falls depends on several factors, including size. Small hailstones (diameter <1-inch), fall between 9 and 25 mph. The 1-inch to 1.75-inch diameter hailstones seen in a typical severe thunderstorm fall between 25 and 40 mph. Strong supercells produce 2-inch to 4-inch diameter that can fall at speeds between 44 and 72 mph.

Exceptionally large hailstones with diameters exceeding 4-inches can fall at over 100 mph. The largest hailstone recovered in the United States fell in Vivian, South Dakota, on June 23, 2010, with a diameter of 8 inches and a circumference of 18.62 inches. It weighed 1 lb. 15 oz!

The Shot

Most of a storm chasing trip is driving. Typically, you get to a safe, photogenic location and have minutes to take a picture before driving to a new location. Very occasionally, you get a slow-moving supercell that you can watch for an hour or so.

This cell was moving at 45 mph se we only had a few minutes to appreciate the hail roar and the storm’s beauty before leaving. This supercell was dying, and we needed to drive 50 miles to our next location to pick up a new line of storms that were forming.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck

PS Thanks to Allan Fisher for reviewing my meteorology!