Hoodoo. A Rock or a Spell?

Hoodoo has three meanings. As a noun, it’s either a fantastical pillar of rock or a religion characterized by sorcery and spirit possession. As a verb, it means to bewitch or to cast a spell.

It’s fantastical rocks when visiting Bryce Canyon National Park in Utah. But at times, you also feel bewitched amongst the majestic hoodoos.

Utah, and specifically Bryce, has the largest number of hoodoos in the world. There are twelve hoodoo amphitheaters in the park with thousands of hoodoos to admire.

How Did They Form?

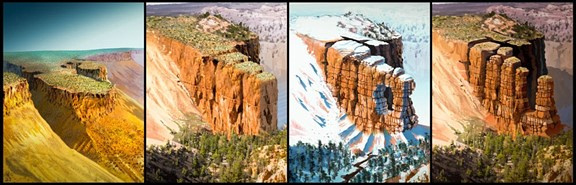

Paiutes lived in the park when Euro-Americans arrived in southern Utah. They explained the colorful hoodoos as “Legend People” who were turned to stone by a coyote. We now know that over millions of years, a plateau was transformed into the hoodoos of Bryce Canyon.

It was a combination of water, freezing and thawing, variations in the type of rocks, and slightly acidic rain that created Bryce. The area receives approximately 100 inches of snowfall and undergoes roughly 200 freeze/thaw cycles a year. Snowmelt seeps into joints and cracks in the rocks. When it freezes and expands, it forms an ice wedge that widens the space.

In time, it breaks the rock. Fragments of rock ranging in size from pebbles to Volkswagen-size boulders fall away to the canyon floor, slowly forming hoodoos. The undulating shapes are caused by the different erosion rates of the four types of rock in the spires.

Limestone, siltstone, and dolomite are the hardest rocks. It takes ice wedges to erode them. They form a protective caprock on most spires. Mudstone is the softest. It easily erodes when wet, running down the sides of the spires forming a protective mud stucco coating.

All the rocks contain abundant calcium carbonate. Even slightly acidic rain is enough to dissolve the calcium carbonate that holds these rocks together. Variations in the amount of calcium carbonate control how easily dissolvable (or how resistant) that rock layer is.

From a plateau, eventually the rocks break down into walls, windows, and then as individual hoodoos. Brian Roanhorse/NPS

The Shot

In July, I joined three Naperville Camera Club members on a trip to the Southwest. Among our many stops was Bryce. I had been there about ten years ago but wasn’t satisfied with my images from that trip.

The morning sky wasn’t that interesting, so fellow photographer Steve Horne and I decided to hike the Queen’s Trail down to a distinctive hoodoo named Thor’s Hammer. It’s the one that clears the horizon in the picture.

Checking an iPhone app, we knew that the sun would rise just to the right of Thor’s Hammer. When the sun is peeking past an edge like the horizon, the light passing through the lens aperture blades can create a visually interesting sun star.

We tripped our shutters at just the right moment to capture a sun star. And at the same time, red reflected light made the rocks in front of us a radiant, glowing red.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus