A Survivor

Very few buildings survived the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Old St. Pat’s Catholic Church is one of them. The fire missed the church by a mere two blocks. It became the oldest public building in the City of Chicago.

Irish immigration to Chicago began in the 1830s. Arrivals grew exponentially following serial potato crop failures beginning in 1845. By 1860, Chicago had the fourth largest Irish community in the country.

The same religious divisions in Ireland traveled to America along with the immigrants. Protestants separated themselves from Catholics by both religious identity and by socioeconomic class.

Irishness in Chicago became synonymous with Catholic, working-class, and poor. Prejudice against Irish immigrants led to pervasive social stereotyping. It wasn’t until 1997 that the Chicago City Council exonerated Mrs. O’Leary and her cow of all guilt for starting the Great Chicago Fire.

Chicago’s Irish Catholic immigrants needed their own church. Irish bishop William Quarter met that need by founding Old St. Patrick’s Church on Easter morning of 1846. Named for the patron saint of Ireland, it was the first English-speaking Roman Catholic church in Chicago.

A humble wooden building at the intersection of Randolph and Desplaines Streets served the parish for ten years. A larger replacement was needed, and two of Chicago’s earliest practicing architects, Augustus Bauer and Asher Carter designed the current church.

The cornerstone was laid for the new building on May 23, 1853. It was constructed of yellow Cream City brick from Milwaukee. After three and a half years of work, the current Old St. Pat’s was dedicated on Christmas Day 1856.

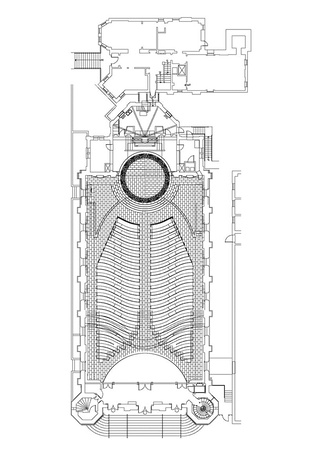

Most Catholic churches feature a prominent crucifix. But not Old St. Pat’s. Look at the floor plan.

The center aisle and the steps to the altar create a cross. And the curving, tapering pews represent the ribs of Christ on the cross. Take another look at the photo.

The center aisle and the steps to the altar create a cross. And the curving, tapering pews represent the ribs of Christ on the cross. Take another look at the photo.

A New Life

Old St. Pat’s was never located in a fashionable residential neighborhood. By 1912 the church, located at Adams and Desplaines Streets, was surrounded by a skid row, manufacturing buildings, and warehouses.

Most churches in this situation would have been abandoned. But in Chicago, the Catholic connection to sacred spaces defies economics.

Thomas A. O’Shaughnessy, an illustrator for the Chicago Daily News, breathed new life into the city’s oldest public building. He was hired to redecorate the church between 1912 and 1922. His legacy includes stunning, luminous windows of opalescent pastel colored stained glass as well as intricate Celtic stenciling on the walls and ceiling.

The inspiration for O’Shaughnessy’s Celtic design elements came from two sources. The first was the Celtic design on display at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The second was a European trip between 1905 and 1906. While in Ireland, he was drawn to the themes and pattern work in the Book of Kells, a 9th-century illuminated manuscript containing the four books of the Christian gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John).

O’Shaughnessy designed, constructed, and personally installed the beautiful stained-glass windows of Old St. Pat’s between 1912 and 1922. The twelve side windows were inspired by the Celtic designs of Ireland’s Book of Kells.

Three windows are a triptych installed in the balcony of the eastern facade of the church. They are known as “Faith, Hope & Charity” and as the Terrence MacSwiney Memorial Triptych. MacSwiney was an Irish playwright, author, and politician. He served as the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork during the Irish War of Independence in 1920.

O’Shaughnessy personally cut and fit over a quarter million pieces of glass into the lead frames of the MacSwiney Memorial Triptych.

The middle MacSwiney window.

The middle MacSwiney window.

Hard Times

By 1950, Old St. Pat’s was again declining and in danger of demolition. Construction of an expressway split the neighborhood causing parishioners to leave for the suburbs.

Fortunately, Old St. Pat’s was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 avoiding the loss of this architectural gem. But the decline in parishioners continued.

By 1983, there were only four registered members of the church. Reverend John J. Wall became the pastor. He created a “church for the marketplace” plan with strong outreach to young adults. He also launched the Center for Work and Faith, to attract working professionals. In addition, he recruited young adults in local bars.

And in 1985, his first Old St. Pat’s “World’s Largest Block Party” drew 5,000 people to Des Plaines Street. The event helped create financial security for the parish.

The four tactics worked. Just two years later, the church’s mailing list had grown to 10,000 people.

The block party ended its run in 2020. But today, Old St. Patrick’s is home to more than 3,000 households and innumerable friends. The future appears bright.

The Shot

When I went to the balcony for a photo of the MacSwiney Memorial Triptych, I noticed the sweeping view of the church below me. This view seemed to capture the spirit and magnificence of this sacred space.

I’ll be gone next week photographing, so the next Friday Photo will be May 31.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus