The Supercell

Super isn’t an exaggeration. Supercell thunderstorms can tower over the land reaching heights of up to 13 miles. The anvil shaped top can stretch as large as 60 by 180 miles.

May 23, 2016, near Northfield, Texas

Typically no more than twelve miles across at the base, supercells produce severe weather, including damaging winds over 70 mph, very large hail (the record is eight inches in diameter), and sometimes tornadoes. Once formed, they can last for hours.

The difference between a regular thunderstorm and a supercell is the presence of a deep and persistent rotating updraft called a mesocyclone. This rotation produces a stacked plates appearance as seen above.

An Ingredient List

You need four ingredients for a supercell: wind shear, lift, instability, and moisture.

Wind shear is produced by a difference in the speed and direction of wind at different altitudes, typically at 5,000 feet and 20,000 feet. Shear creates rotation of the storm’s updraft, the critical ingredient for supercells.

Wind shear also causes the rotating updraft to tilt. That tilt separates the rotating mesocyclone updraft (red up arrow) of warm, moist air from the downdraft (blue down arrow) of rainy, cold air. Without tilt, cold and warm air mix, ending the storm.

From the University of Arizona

Supercells are most common in the central United States. The Great Plains of the Dakotas, Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas offer unobstructed views of these beasts.

The Shot

On May 19, our storm chasing tour was positioned near Arnett, Oklahoma. The leader picked this supercell as having tornadic potential. But it was a high precipitation supercell that hid any tornadoes inside a torrential downpour.

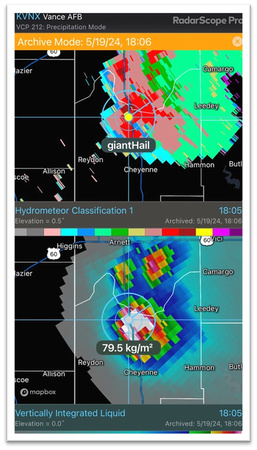

There probably was an unseen tornado hidden in the rain. On radar, the circled area in blue indicates a small debris cloud associated with a tornado. And the second radar image indicates giant hail.

Radar images courtesy of Greg Dutra, ABC 7 Chicago meteorologist and neighbor.

We weren’t disappointed by the lack of a visible tornado. The supercell’s beautiful structure was much more photogenic than a tornado.

After admiring the storm for about a half hour, we returned to the van and chased it until sunset. Then it was time for the long drive to Salina, Kansas, five hours away. After 944 miles of riding in the van that day, crawling into bed at 2:00 am never felt so good.

Thanks for looking,

Chuck Derus